Since 2008, the healthcare industry has been experiencing a pronounced shift toward physician employment. In 2014, only approximately one-third of all physicians were truly independent.2 The majority of newly employed physicians have landed at hospitals or large medical groups (53 percent of physicians in 2014 vs. 38 percent in 2008).3

The aggregating of formerly independent primary care and specialty providers has benefited health systems, including linking new patients to the health system, formalizing referral channels, adding patient access points, generating revenue from hospital-based pricing and facility fees assessed at newly acquired outpatient clinics, and reducing competition on ambulatory services.

However, these benefits come at a price: most health systems are subsidizing their employed physician practices by more than $176,000, triple the median per-physician subsidy as recently as 2004.4

As health systems aggregate physician practices, the ongoing operational subsidies required are not often the focus. In the assimilation and integration phases, health systems must determine how to limit the losses generated by their physician practices.

Much has been written about the need for reduced health system allocations, improved compensation models, better physician productivity, and increased non-physician provider to physician ratios. These changes often require major operational and cultural changes and take years to implement. Moreover, implementing these new operational changes over often hundreds of sites is challenging to accomplish quickly.

Instead, we recommend working on the low-hanging opportunities of practice consolidation first, and then implementing the operational changes. This both allows health systems to capture savings quickly and reduces the cost of implementing other operational changes when the number of sites declines by three or four times (it is a lot easier to implement the same changes in 25 sites than it is in 100).

Case Study: $3B Mountain State Health System

A regional health system with 500 providers was in the process of rapidly growing its employed provider base. At the same time, per-physician subsidy was inhibiting the affordability of acquiring additional providers.

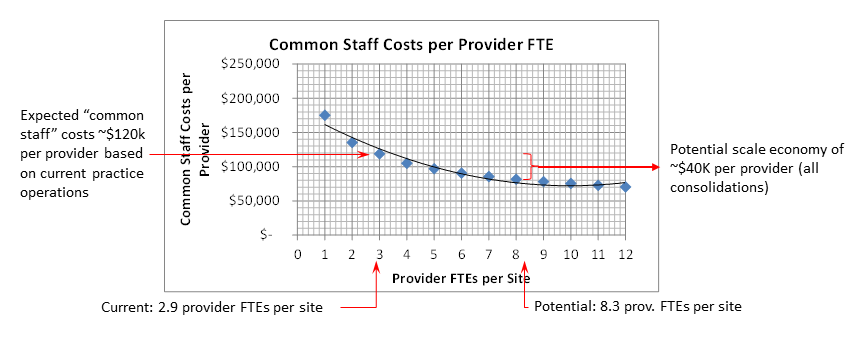

Evaluating the provider group’s configuration showed the 265 market-facing physicians in 90 locations across their metro markets.5 The resulting 2.9 providers per site was consuming facility and supporting personnel at rates far higher than they would in larger settings.

Detailed evaluation showed moving from the current 2.9 providers per site to the health system’s ideal consolidation (for the existing 265 providers) of 8.3 providers per site would save $40,000 per provider annually.

Real Consolidation Savings

The cost savings demonstrated in the case study above came not from radical changes to the operations, but instead from more efficient use of space and common supporting personnel at the health system’s current standards. As a result, these savings are generally “free” to the health system willing to actively look for the savings.

As an extreme example of the cost savings origin consider a practice with 1 provider. This provider needs a clinic with exam rooms and all the supporting space, front desk staff, a medical assistant, a clinic manager, etc. Consider also that a typical provider will have at most 46 weeks of clinical practice. The other six weeks will have the clinic open, staffed, without anyone being seen. This is exacerbated if the provider is a proceduralist and not in clinic full time.

The scale economy opportunity arises from operating multiple small clinics. Most health system did not immediately consolidate clinics as physician practices were acquired. As a result, health systems find themselves operating a growing network of small (often one- to two-provider) clinics.

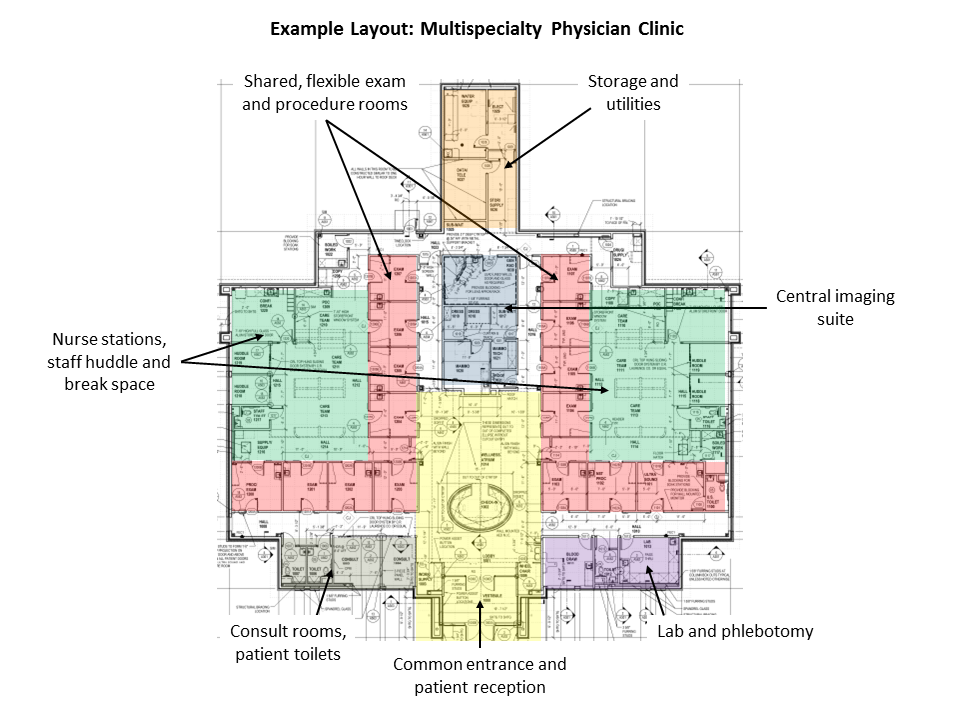

Consolidation of small, dispersed clinics into strategically placed, multi-specialty outpatient centers can create real operational efficiencies. The scale economy from just two elements: support personnel and lease costs, can create savings of $40,000+ per provider annually.

These consolidations often can be achieved with limited upfront capital costs, simply by consolidating multiple clinics into existing sites that have excess physical capacity and timing new leases for larger outpatient centers to coincide with small center lease expirations.

The major obstacles clinic consolidation faces can be mitigated with appropriate planning. These include:

· Balancing scale economy with the desire for multiple access sites

· Long term leases/large lease buyout costs at current sites

· Training reception staff to handle patients for a variety of specialties in one location

· Implementing operational measures to maximize efficient use of square footage

· Cultural adjustments as physicians are incorporated into larger clinics

Cost savings start immediately, helping off-set the short-term obstacles for the current providers. Longer-term, as health systems employ more providers, the cost savings built into the model are multiplied over a larger number of providers. Moreover, population health care models succeed best with multispecialty and multiple provider practices.

Conclusion

Aggregate – assimilate – integrate. The three stages of employed provider group development have unique opportunity. Health systems that have aggregated large employed provider groups should evaluate site consolidation as a first step in their assimilation phase. Those that do so will both save $25,000 – $50,000 per provider annually and, by reducing the number of sites, speed the integration phase.

1 “Aggregate, Assimilate, Integrate – Successfully Building an Employed Physician Group”; Lovrien, Peterson, et al; Becker’s Hospital Review, May 2013

2 Accenture Physicians Alignment Survey, 2012

3 The Physicians Foundation 2014 Survey of America’s Physicians

4 MGMA median health system employed physician subsidy

5 Market-facing providers are defined as those having a direct, ambulatory relationship with patients in locations off the hospital campuses. As a result it does not include employed providers such as hospitalists, emergency room physicians, anesthesia, etc. Additionally, this analysis did not evaluate the rural markets which often do not have consolidation opportunities due to the limited numbers of providers needed.

The views, opinions and positions expressed within these guest posts are those of the author alone and do not represent those of Becker’s Hospital Review/Becker’s Healthcare. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them.