The universe and variations of clinically-integrated networks, accountable care organizations, hospital-physician co-management arrangements, hospital-physician shared savings arrangements, gainsharing arrangements and other types of quality and value-focused ventures is expanding and evolving, as are questions about how such ventures should be structured and implemented. As is the case in nearly every industry and circumstance, the most complex and hotly debated questions relate to the flow of money — who will receive remuneration for what under which circumstances.

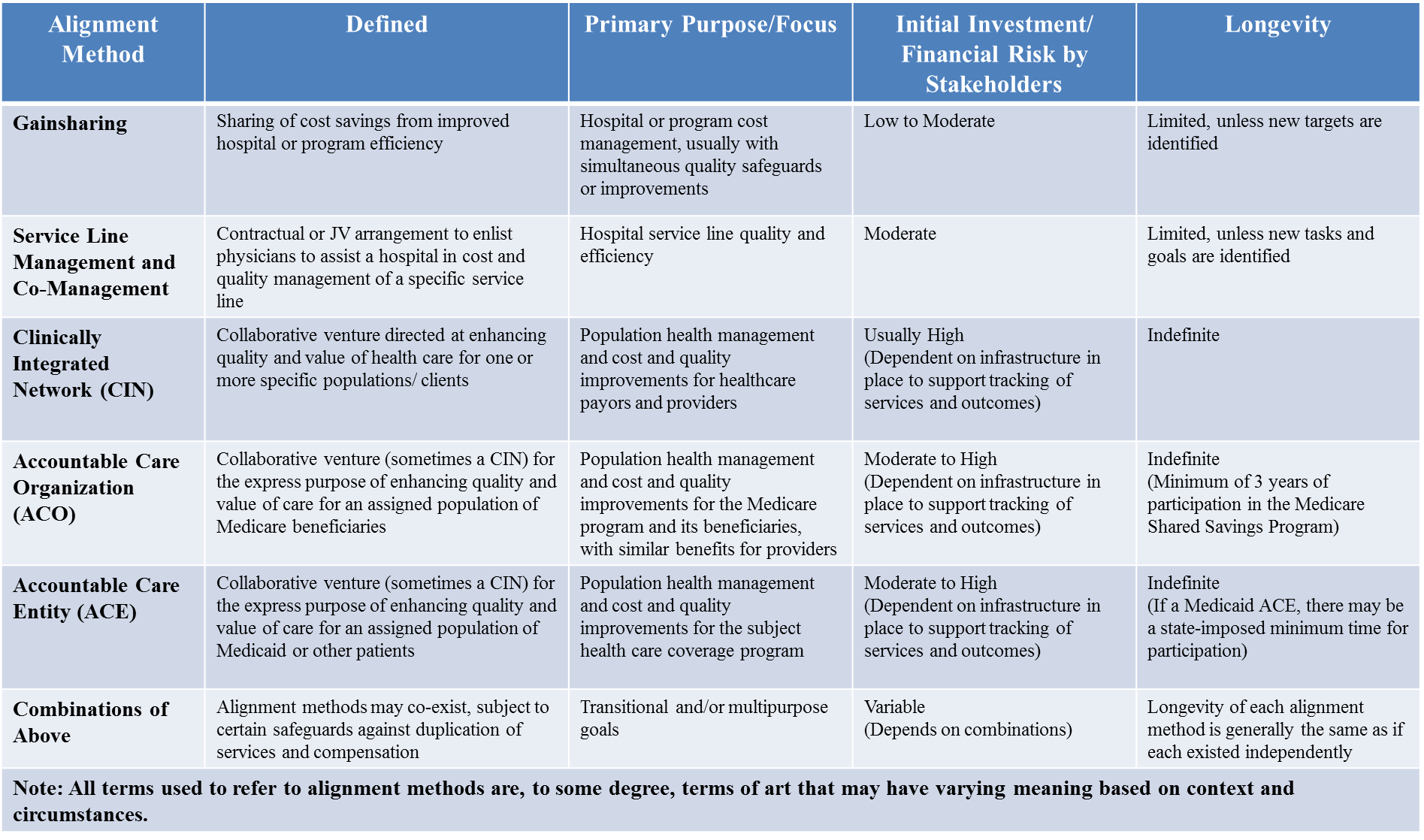

Table 1 – Examples of Common Alignment Strategies for Achieving Quality and Value[i]

The role of physicians in achieving hospital quality

Historically, physicians have been viewed as the primary drivers of patient care processes. They are, to some degree, the captains-of-the-ship[ii] whose orders and actions determine the type and extent of services provided to each patient. Legally and culturally, they may have the most accountability for individual patient outcomes. For these reasons, the leadership, input and cooperation of physicians is usually regarded as essential for effectuating changes in care processes and delivery. For hospitals facing negative financial consequences if new payer measures of quality and value are not achieved, changes in care processes and delivery may be important to future survival and success, and the engagement of physicians to transform care processes is a reasonable if not imperative proposition.

But what does it mean to engage physicians to transform care processes? Does engagement reasonably or necessarily involve payment to the physicians? If so, can the payments reasonably be characterized as compensation for “services” if they are contingent on a result (such as achievement of quality and value targets) rather than hours of effort that can be objectively measured? How does one measure and quantify the value and appropriate compensation for such services?

The importance and challenge of ensuring fair market value

In the current regulatory environment, in which financial relationships with physicians — including most compensation arrangements — implicate a complicated patchwork of state and federal laws and regulations, and the stakes for violating any those laws and regulations can be very high, or even financially disastrous[iii], these are tricky questions.

They are especially tricky given that: (a) legal and regulatory compliance often hinges on establishing that any remuneration flowing between physicians and hospitals is fair market value and commercially reasonable compensation for actual, legitimate and necessary items or services[iv]; and (b) the prevailing understanding of “fair market value,” “commercially reasonable” and “legitimate” items and services has developed around volume-based compensation (i.e., more items or services personally provided = more compensation, rather than fewer items and services provided but better coordination and outcome = more compensation). Complicating things further is the fact that courts and enforcement agencies might reject opinions of fair market value and commercial reasonableness if they determine that they don’t reflect proper consideration of the actual facts, circumstances and applicable law.[v] As acknowledged recently by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which is the Federal agency charged with enforcing the strict-liability Stark Law:

Entities furnishing DHS [including hospitals furnishing inpatient and outpatient services] face the predicament of trying to achieve clinical and financial integration with other healthcare providers, including physicians, while simultaneously having to satisfy the requirements of an exception to the physician self-referral [AKA Stark] law’s prohibitions if they wish to compensate physicians to help them… structuring incentive compensation and other payments can be particularly challenging for hospitals, even where the payments are to hospital-employed physicians.[vi]

Three factors that may affect value in a quality or value focused arrangement

Below are three factors that may affect the determination of fair market value and commercial reasonableness in a quality or value-focused arrangement.

1. Appropriately defining the arrangement: Sometimes, the purposes and nature of an arrangement are straightforward and easily articulated. For example, a hospital may enter into an hourly compensation arrangement with a physician to serve as the hospital’s quality director, with duties that include collecting and reviewing clinical quality data, and communicating that clinical quality data to hospital managers and other physicians during monthly meetings.

On the other hand, an arrangement to pay a group of physicians for achieving “quality” or “cost savings” is more nebulous. The value in achieving the “quality” or “cost savings” can vary, depending on: (a) what is involved in attaining the achievement, and/or (b) what the hospital will gain (or what loss it will avoid) from the achievement. The value may vary with the specific activities and criteria that trigger the payments, so good information about the details and purposes of an arrangement — about who will do or provide what and why — will help ensure an accurate and reliable assessment of fair market value, and commercial reasonableness. This information may require some careful thought to appropriately articulate.

2. Identifying applicable law: There are various laws and regulations that may affect the goods and services for which parties may permissibly provide or accept remuneration, what form the remuneration may take, and how or if a specific definition of fair market value applies. If an assessment of fair market value and commercial reasonableness is to assist with regulatory compliance, it reasonably shouldn’t include the assignment of value for activities or items that are prohibited or otherwise proscribed by applicable laws and regulations. Caution is warranted in selecting comparables when different laws and regulations may apply based on different circumstances and jurisdiction. Knowledgeable counsel can assist in identifying and interpreting applicable laws and regulations, and can be helpful in appropriately defining the arrangement as well as communicating the applicable laws and potential valuation pitfalls to a valuation analyst.

3. Other arrangements or payments: Hospitals might pursue their quality and value goals from multiple angles simultaneously. They may implement employee bonus programs that provide for incentive compensation to employed practitioners for achievement of specific quality and efficiency goals. They may have service-line co-management agreements, gainsharing agreements and/or a “hospital quality and efficiency program” providing compensation for development and achievement of departmental or hospitalwide quality and efficiency targets. They may sponsor and/or participate in an ACO or clinically integrated network that distributes money to participating physicians and other providers as compensation or incentive for achievement of quality and cost-reduction targets. Given the importance and complexity of creating and reinforcing changes in provider behavior, the co-existence of multiple quality and value-focused arrangements is common and generally reasonable. Separate remuneration for related but distinct items or services is also generally reasonable. However, duplicative renumeration — meaning multiple payments for the same thing from the same or different sources — are generally fair market value and commercial reasonableness pitfalls.

In a Federal False Claims Act case that settled for $21.75 million in early 2015, the qui tam relator alleged violation of the Stark Law and Anti-Kickback Statute through a hospital’s payment of $1,000 per day for “medical directorship” (quality supervision) duties that allegedly did not involve any legitimate additional work or responsibilities in excess of those that physicians performed (and for which they received professional fees) when performing screening colonoscopies. The essence of the allegation was that the medical director compensation was not fair market value and not reasonable because it was duplicative of other payments. If the hospital or physicians obtained valuation analysis for the questioned services (and it is not clear whether they did or did not), the outcome of that valuation analysis would be most reliable if it examined and accounted for the need, reasonableness and incremental value of the medical director services in the context of the other services being provided.

Arrangements to promote quality and value in healthcare are varied and complex and may be overlapping, making the process of determining the fair market value and commercial reasonableness of such arrangements daunting and perplexing. Regardless, fair market value and commercial reasonableness may be requirements for regulatory compliance, making their accurate determination an imperative. The considerations identified here should be of assistance for demystifying how and why certain details of arrangements may influence the process and outcome of a valuation analysis.

[i] This table is adapted from one that was presented in a webinar presentation that the author performed with others for Strafford Publications.

[ii] This is a reference to the legal doctrine introduced in McConnel v. Williams (361 Pa. 355, 65 A.2d 243, 246 (1949)), which holds that, in most circumstances, the physician of record is legally responsible for what happens in their operating room, or, when more broadly interpreted, for whatever happens on their “watch.”

[iii] For examples of recent cases of hospital liability, see U.S. ex rel. Drafeford v Tuomey Healthcare System, Inc. (which resulted in a $237.5 million verdict against the hospital that was upheld by an appeals court); and U.S. ex rel. Baklid Kunz v. Halifax Hospital Medical Center et al (which ended with an $85 million payment by the hospital to settle Stark Law claims, after the hospital reportedly incurred nearly $21 million in legal fees).

[iv] See the Office of Inspector General’s Supplemental Compliance Program Guidance for Hospitals (2005), stating“The general rule of thumb is that any remuneration flowing between hospitals and physicians should be at fair market value for actual and necessary items furnished or services rendered based upon and arm’s length transaction and should not take into consideration, directly or indirectly, the value or volume of any past or future referrals or other business generated between the parties.” [70 Fed Reg. 4866 (January 31, 2005)].

[v] See 69 Fed. Reg. 16054, 16107 (March 26, 2004), stating “[w]hile good faith reliance on a proper valuation may be relevant to a party’s intent, it does not establish the ultimate issue of the accuracy of the valuation itself.” Consider also that courts rejected the validity of fair market value and commercial reasonableness opinions obtained by the hospital defendants in the Tuomey case and other False Claims Act cases, such as U.S. ex rel. Singh v. Bradford Regional Medical Center.

[vi] 80 Fed. Reg. 41686, 41928 (July 15, 2015)

Among hospitals, new Medicare and other payer policies have focused attention on measures of “quality” and “value.” Among some, the new focus on quality and value is viewed as the steam engine for transformation and innovation in relationships with physicians and other providers. Among others, it is viewed as a change in the language of business, giving new names and life to old ideas and strategies that, for one reason or another, fell out of favor previously but have returned to the limelight in a cyclical fashion. Although the extent to which ideas are new or old may be debatable, one effect of assimilating quality and value into the lexicon of hospital operators has been clear: an increase in transactional activity that is focused on securing alignment, collaboration and clinical integration with physicians.

The universe and variations of clinically-integrated networks, accountable care organizations, hospital-physician co-management arrangements, hospital-physician shared savings arrangements, gainsharing arrangements and other types of quality and value-focused ventures is expanding and evolving, as are questions about how such ventures should be structured and implemented. As is the case in nearly every industry and circumstance, the most complex and hotly debated questions relate to the flow of money — who will receive remuneration for what under which circumstances.