Source: CB Insights: “Big Auto’s Scramble for Auto Tech Partnerships, Investments, and M&A,” Aug. 25, 2016. Used with permission.

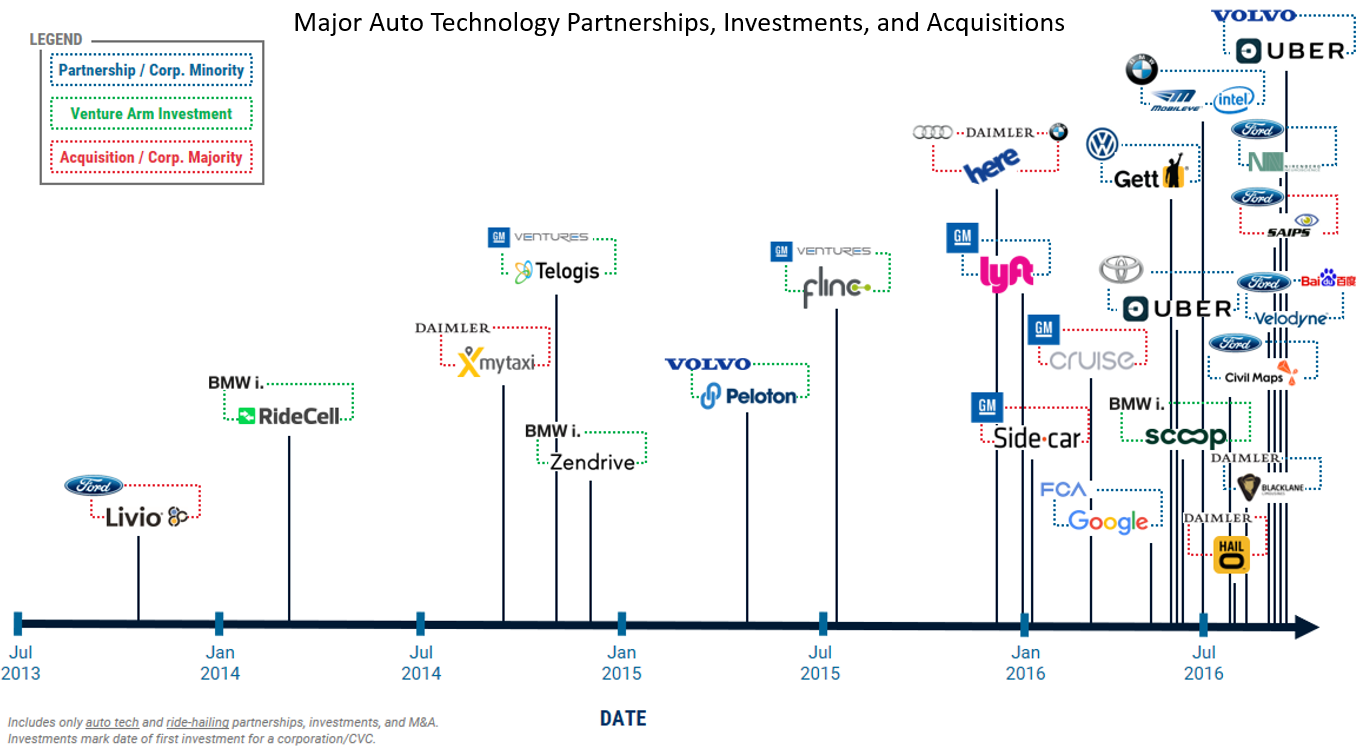

As this timeline illustrates, within just three years the automobile technology sector has gone from a relatively open road to a traffic jam of deals among legacy carmakers, innovative startups, ride-sharing companies, autonomous technology suppliers, and technology giants.1

When entrepreneurial imagination, new technology, changing consumer expectations, and legacy vulnerabilities converge, a flurry of activity is unleashed that can undermine even the most firmly entrenched behaviors and economic relationships. Although U.S. automobile sales have increased 70 percent since the financial crisis and achieved a 15-year high in 2015, multiple indicators suggest that unprecedented change is coming, and innovators and legacy companies alike are moving rapidly to position themselves for a transformed business model.2

A closer look at what’s happening in the automobile industry reveals lessons about the power of disruption that go to the heart of today’s healthcare environment.

At the outset, let’s consider three foundational truths about cars that until recently seemed almost too obvious to state:

Americans love to own cars

Cars are driven by people

Cars are made by car companies

It turns out that these obvious truths are not so true after all.

Truth #1: Americans Love to Own Cars

The American car culture is legendary. I remember my first car—a Buick Skylark convertible—and the sense of freedom it brought. However, car ownership may not offer quite as much freedom as America’s eulogized car culture would suggest.

The average price of a new car in America is $33,000. In addition, we pay almost $9,000 per year in depreciation and expenses like gas, maintenance, and finance charges.3 On average, we spend 33 hours per year in traffic delays—61 hours if you live in San Francisco. In certain parts of Los Angeles, you can spend 90 minutes to drive just 26 miles. If you live in Chicago, you’ll find less than one parking lot for every 1,000 commuter cars. And if you live in Boston, your likelihood of having an accident is almost 160 percent compared with the national average.4

In the face of these inconveniences, car ownership in America is declining. All the major indicators of vehicle ownership—vehicles per household, per licensed driver, and per person—peaked between 2001 and 2006, with the number of vehicles per household decreasing from 2.05 in 2006 to 1.8 in 2013.5

For millennials, research has attributed this decline to economic pressures, lifestyle preferences, and the entrance of ride-sharing companies like Uber and car-sharing services like Zipcar.6 As of June 2016, Uber had provided 2 billion rides (just six months after reaching the one billion-ride milestone).7 Zipcar has more than one million members and operates in more than 500 cities.8

Reading books didn’t seem inconvenient until Kindle came along. Television didn’t seem inconvenient until streaming video came along. With the emergence of viable alternatives, car ownership too is looking less attractive. Now that this door has been opened, the rush toward disruption has begun in full force.

Truth #2: Cars Are Driven by People

The most fundamental notion around any form of transportation is that someone is in the driver’s seat. However, the breakthrough idea of a driverless car coupled with technology that allows cars not only to sense their surroundings but to learn from experience and communicate with one another could bring about a profound, almost unimaginable, change in our lives and economy.

Consumer acceptance of this idea has been rapid. According to a 2016 survey by AlixPartners, almost three-quarters of respondents want self-driving cars “to take over all their driving needs.” About 90 percent said they would want a partially self-driving car.9 Between 2012 and 2016, the Ford Motor Company went from viewing self-driving cars as a “frivolous Silicon Valley moonshot” to announcing that it would mass-produce a self-driving car for commercial ride-sharing by 2021.10 A new self-driving car advocacy group formed by Google, Uber, Lyft, Ford, and Volvo highlights the diversity of stakeholders pushing the adoption of this new technology.11

The full implications are hard to imagine, but the potential benefits are clear: more productivity, greater convenience, lower expenses, less pollution, and safer roads.

Truth #3: Cars Are Made by Car Companies

Until recently, the idea of competing with one of the major automakers was unthinkable. The necessary capital, expertise, and infrastructure to be viable in a mature industry were just too big a barrier. However, all that has changed with the convergence of several forces.

First is the decline in demand for traditional cars, reflecting emerging dissatisfaction with their expense, inconvenience, and environmental impact.

Second is the emergence of new technology that facilitates new approaches to mobility, from the use of beacon and mapping technology for ride-sharing apps to the application of LiDAR (light detection and ranging) systems and machine thinking for self-driving cars.

Third is the vulnerability of legacy carmakers, including high fixed costs, cumbersome leadership and management structures, and lack of demonstrated capability to innovate.

Fourth and perhaps most important is the broadening of thinking from cars to mobility. This new thinking changes the business question from how to sell cars to how to get people from place to place in the most efficient way with the most positive experience.

The convergence of these factors has completely changed the competitive dynamic of the auto industry—or rather, the mobility industry. CB Insights reports that 33 companies are working on self-driving cars, including traditional car companies like BMW and Honda along with tech companies, ride-sharing companies, and supply companies.12 The list includes huge players like Apple and Google along with startups. A web of affiliations is forming as established companies attempt to secure new capabilities, startups attempt to secure capital and market share, and various firms attempt to position themselves as suppliers of underlying technology to all carmakers.

The Legacy Dilemma

In this environment, legacy carmakers have certain strengths—primarily market share and size. They are working hard to leverage those strengths to fulfill what they lack in innovation and next-generation technology. Within just one month, Ford invested in LiDAR sensor company Velodyne, machine learning company SAIPS, 3D mapping company Civil Maps, and machine vision company Nirenberg Neuroscience.13

At Ford, there has also been strong leadership focus on something that legacy companies have notoriously lacked: the ability to change dramatically and rapidly. In January 2015, the company announced its smart mobility plan and “25 global experiments designed to change the way the world moves.”14 In making the announcement, Ford CEO Mark Fields said, “As we drive innovation in every part of our business…we are determined to learn, to take risks, to challenge custom and question tradition, and to change our business going forward.”15 In March of 2016, Ford announced creation of a smart mobility subsidiary designed to “compete like a startup company.”16 Five months later, Ford announced its 2021 goal for self-driving cars along with plans to double subsidiary staff.17

For all its leadership focus, investment, and legacy strength, Ford faces strong headwinds to becoming a leader in the new mobility industry.

With a new group of competitors including Google, Uber, and potentially Apple, Ford is facing off against companies with orders of magnitude more capital, vast technology expertise, and a record of innovation and disruption. In addition, every other major carmaker is also pursuing self-driving cars with a similar partnership strategy.

By some measures, Ford could be seen as playing catch-up. Google’s self-driving cars have already driven 1.5 million miles.18 Even with the doubling of Ford’s mobility subsidiary staff, it has less than one-eighth the employees of electric car startup Faraday Future.19

Finally, even if Ford succeeds in its quest to lead the mobility industry, the company still is faced with the challenge of replacing the revenue lost in a new business model that by definition will have less car ownership. In this new era, even a successful Ford likely will be a smaller company.20

Ford is promising to disrupt itself. However, the list of legacy companies that have been able to self-disrupt is very small indeed.

Themes of Disruption

The themes revealed by disruption in the $2 trillion auto industry are strikingly similar to those in our nation’s $3 trillion healthcare industry.

Disruption undermines fundamental relationships. Since the dawn of transportation, humans have controlled vehicles. Soon, they will not. For hundreds of years, the basis of healthcare has been a face-to-face visit between a doctor and patient. Telemedicine, remote monitoring, expansion of advanced practice nursing, and other innovations are changing that core relationship.

Disruption reveals inconveniences that a consumer may have only partially perceived. Even America’s love of cars cannot overcome the drawbacks of car ownership now that alternatives are emerging. Healthcare’s many inconveniences make it highly vulnerable to options that improve access, reduce paperwork, enhance communication, and otherwise create a more contemporary experience.

Disruption is fueled by breakthrough technology. Cloud computing, beacon technology, 3-D mapping, and advanced sensors are allowing self-driving cars to navigate streets and ride-sharing companies to deliver a car to you at the touch of a button. In healthcare, we are seeing live video, wearable and ingestible sensors, robotic checkups, cellular-level repair, and many other technologies begin to fundamentally change the way patients are diagnosed, treated, and monitored.

Disruption introduces powerful new competitors with new capabilities. For carmakers, many of the new competitors are not other carmakers, but innovative technology companies—in some cases, huge technology companies. In healthcare, physicians and hospitals traditionally have controlled much of how healthcare is delivered. Increasingly, big data companies, large pharmacy chains, technology giants, large insurers, and big pharma will be using their strengths in innovation, data analytics, care management, high access, digital connectivity, consumer experience, and precision medicine to draw the loyalty of healthcare consumers.

Disruption introduces a broader view of consumer expectation. At one time, the purpose of a carmaker was to make cars. Disruption revealed that what consumers really want is mobility through the most efficient means. The traditional purpose of a healthcare organization has been to care for people who are sick or injured. A broader view is to help people access and coordinate the full range of resources that they need to stay healthy.

Once entrepreneurial imagination, new technology, consumer expectations, and legacy vulnerabilities converge, change comes at an intense pace. Newspaper advertising revenue declined by half within two years.21 Blockbuster went from $6 billion in annual revenue to bankruptcy within six years.22 Uber went from startup to serving 450 cities worldwide within seven years.23 And in just three years, self-driving cars have gone from a curiosity to an imperative for legacy carmakers.

In healthcare, we are seeing similar evidence of rapid change. Between 2006 and 2014, the number of retail clinics grew 445 percent.24 Within just two years, Walgreens became the nation’s number-two provider of flu shots.25 The global telemedicine market is projected to grow at a rate of almost 20 percent annually between 2016 and 2021.26 Within one year, IBM invested more than $4 billion in IBM Watson Health.27 Within a three-week period in 2015, three major health insurance company mergers were announced for a total of $97 billion.28

It is not clear whether Ford’s strategy will successfully guide the company from the era of cars to the era of mobility. However, Ford has taken an essential first step: It has accepted that the industry’s business model and conditions are changing in an unprecedented way.

Although healthcare is not yet in the throes of disruption at the level of self-driving cars, the industry is clearly moving in that direction. To prepare, healthcare organizations need to recognize what Ford has recognized: Only by accepting that fundamental change is coming can healthcare organizations move with necessary urgency to prepare for that change.

1 CB Insights: “Big Auto’s Scramble for Auto Tech Partnerships, Investments, and M&A.” Aug. 25, 2016.

2 Ingrassia, P.: “Hail, Mary.” Fortune, Sept. 15, 2016; Spector, M. et al.: “U.S. Car Sales Set Record in 2015.” The Wall Street Journal, Jan. 5, 2016.

3 Lee, J.: “What Is the Total Cost of Owning a Car?” Nerd Wallet, Sept. 15, 2016.

4 Chu, J.: “Worst Cities for Car Drivers.” Nerd Wallet, May 4, 2015; Barragan, B.: “The Worst Day and Time to Drive on Every Los Angeles Freeway.” Curbed Los Angeles, Aug. 27, 2015; Hofherr, J.: “Bostonians Crash More Than Twice as Often as the Average Driver.” Boston.com, Sept. 3, 2015.

5 Cohn, D.: “Data Show a Dent in Americans’ Love for Cars.” Pew Research Center, July 1, 2013; “Car Ownership in U.S. Cities Map,” Governing, accessed Sept. 2, 2016

6 Dutzik, T., Inglis, J., Baxandall, P.: Millennials in Motion, Frontier Group, U.S. PIRG Education Fund, Oct. 2014.

7 Somerville, H.: “Uber Reaches 2 Billion Rides Six Months after Hitting Its First Billion.” Reuters, July 18, 2016.

8 Zipcar: “Zipcar Drives Past Million Member Milestone.” Press release, Sept. 8, 2016.

9 Naughton, K.: “Three-Quarters of U.S. Drivers Say They’d Cede Wheel to Robot.” Bloomberg, June 29, 2016.

10 Griffith, E.: “Who Will Build the Next Great Car Company?” Fortune, July 1, 2016; Sage, A. Lienert, P.: “Ford Plans Self-Driving Car for Ride Share Fleets in 2021.” Reuters, Aug. 16, 2016.

11 Griffith (July 1, 2016)

12 CB Insights: “33 Corporations Working On Autonomous Vehicles.” Aug. 11, 2016.

13 Ford Motor Company: “Ford Targets Fully Autonomous Vehicle for Ride Sharing in 2021; Invests in New Tech Companies, Doubles Silicon Valley Team.” Press release, Aug. 16, 2016.

14 Ford Motor Company: “Ford at CES Announces Smart Mobility Plan and 25 Global Experiments Designed to Change the Way the World Moves.” Press release, Jan. 6, 2015.

15 Ford Motor Company: “Remarks: Mark Fields: 2015 Consumer Electronics Show.” Jan. 6, 2015.

16 Ford Motor Company: “Ford Smart Mobility LLC Established to Develop, Invest in Mobility Services.” Press release, March 11, 2016.

17 Ford Motor Company (Aug. 16, 2016)

18 “Google Self-Driving Car Project.” Google.com, accessed Sept. 16, 2016.

19 Rogers, C.: “Detroit Battles for the Soul of Self-Driving Machines.” The Wall Street Journal, June 12, 2016.

20 Griffith, June 29, 2016.

21 Edmonds, R.: “Newspapers Report Ad Revenue Loss for 25th Quarter in a Row.” Poynter, Nov. 26, 2012.

22 O’Neill, M.: “How Netflix Bankrupted and Destroyed Blockbuster.” Business Insider, March 1, 2011.

23 Somerville, H. (July 18, 2016)

24 Boston, D., Bhansali, B.: “US Retail Health Clinics Expected to Nearly Double by 2017 According to Accenture Analysis.” Accenture, 2015.

25 “Walgreens Historical Highlights.” Walgreens.com, accessed Sept. 17, 2016; Frost, P.: “Flu Shots Drive Traffic for Pharmacies.” Chicago Tribune, Sept. 21, 2012.

26 Global Telemedicine Market-Growth, Trends and Forecasts (2016-2021). Mondor Intelligence, Aug. 2016.

27 Japsen, B.: “IBM Watson to Buy Truven Health for $2.6 Billion, Bolsters Data Cloud.” Forbes, Feb. 18, 2016.

28 Banerjee, A., Pierson, R. “Anthem to Buy Cigna, Creating Biggest U.S. Health Insurer.” Reuters, July 24, 2015; Bray, C., Abelson, R. “Aetna Agrees to Acquire Humana for $37 Billion in Cash and Stock.” The New York Times, July 3, 2015; Tracer, Z.: “Centene to Buy Health Net in $6.3 Billion Health-Care Deal.” Bloomberg Business, July 2, 2015.

The views, opinions and positions expressed within these guest posts are those of the author alone and do not represent those of Becker’s Hospital Review/Becker’s Healthcare. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them.