Stipends paid by a hospital can amount to several millions of dollars annually to anesthesiology, emergency medicine, and hospitalist groups. In some cases, stipends paid by a hospital exceed the professional collections groups receive.

It’s understandable that stipends are necessary in facilities with a high percentage of low- and nonreimbursed care or in rural areas where volume is insufficient to support the full-time coverage that is needed. Of course, many hospitals are able to obtain coverage without paying any stipend. In reality, the correlation between reimbursement or payer mix and the stipends paid by hospitals is not as strong as would be expected. Hospitals in markets with a high percentage of commercially insured patients often pay stipends just as large as some safety net facilities. But why?

Many health systems struggle with establishing a consistent, effective approach to contracting with physicians for hospital-based services. As a result, the cost to procure physician services varies greatly, the effectiveness of medical groups and individual physicians is inconsistently monitored and managed, and coordination and integration between the hospital and medical group are suboptimal.

However, health systems can optimize their professional services agreements (PSAs) with medical groups for hospital-based services and achieve substantial savings, enhance outcomes, and better serve their communities by:

» Establishing a preferred staffing and coverage model.

» Regionalizing and standardizing PSA management.

» Paying for performance.

Establishing a Preferred Staffing and Coverage Model

Defining the most appropriate mix of providers and coverage hours is the first step to achieving operational and financial success with hospital-based services. The staffing model directly impacts the cost to the group providing the service to the hospital and, as a result, the stipend the group may be seeking from the health system.

But how do you know if you have the right number and mix of providers? And are they available at the right times? Health systems should evaluate whether the current staffing models fulfill the needs and goals of their hospitals and assess opportunities to reduce costs or improve efficiency through adjustments to staffing and scheduling.

For example, an assessment of the performance of anesthesiology services should include the following:

1. An analysis of operating room (OR) efficiency metrics to understand their impact on the performance of the anesthesiology services and implications for the coverage model, including:

a. Overall Volume and Mix: Higher volume is typically accompanied by more efficient use of anesthesiology providers.

b. OR Prime-Time Utilization (target >80%): Below-average utilization indicates there is ex-cess capacity in the schedule relative to case volumes, typically resulting in too many anesthesiology providers.

c. Turnover Time (target 25 to 30 minutes): Long turnover times reduce the productivity of anesthesiology providers.

d. First Case On-Time Starts (target >85%): It’s rare that a case doesn’t start on time be-cause anesthesia is late. Rather, factors within the surgeon’s control are the most preva-lent cause. Poor on-time starts damage the productivity of anesthesiology providers.

2. An analysis of anesthesiology provider productivity relative to benchmarks to gain a comprehen-sive understanding of performance, including:

a. Cases per Provider: These are a valuable, although incomplete, measure of productivity, because they does not account for patient acuity.

b. American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Units: These units form the basis for most anesthesiology professional fee reimbursement and are a reliable indicator of work effort.

c. ASA Units per Case: These provide an indication of the average acuity of patients.

d. Collections per Provider and per ASA Unit: Collections are greatly influenced by payer mix, commercial rates, and billing office performance.

3. A comparison of current staffing ratios to available benchmarks and comparable peer institutions, including:

a. Anesthesiologist-to-CRNA staffing ratios

b. On-call coverage obligations and requirements

c. Administrative requirements

A similar process would be followed for other hospital-based services. After that, the health system is ready to work with the medical group to establish a staffing model that balances the supply of providers with the demand for their services—not too many that individual productivity suffers and not too few that providers are overworked or cannot meet the access and response time expectations of the organization.

Regionalizing PSA Management

Moving PSA management to a system-level function supports the following:

» Consolidation of multiple contracts with the same medical group

» Coordination with system-wide strategic priorities

» Standardization of terms and provisions

It’s not unusual to come across a health system that has a contract in which it pays a stipend to a large medical group for coverage at one of its hospitals while also having a contract with the same group for coverage at another hospital where no stipend is paid. The lack of a stipend at the second facility is an indication that the medical group’s collections are sufficient to cover its costs at that facility. Sometimes collections are much more than sufficient to cover costs. Let’s say the stipend at the first hospital is $1 million, which allows the group to cover its costs. Meanwhile, at the second facility, the group’s collections exceed its costs by $1 million. The result is that the health system is paying the group $1 million more than is necessary to make the group whole across the two facilities. Although this concept may seem obvious, it is not until contracts are managed at a regional or system level that the financial savings opportunity to the health system becomes apparent.

Alignment is achieved when both parties understand each other’s strategic priorities and structure their relationship in support of those priorities. Unfortunately, PSAs are frequently fragmented, one-off deals with no clear alignment with the broader strategies or priorities of the organization. They are generally loosely managed until it is time to renegotiate and renew or extend the arrangement, and management often lacks the necessary coordination for effective PSA development and negotiation. By consolidating contracts and raising the level of communications to a system level, the health system and medical group are better enabled to establish mutually beneficial arrangements that positively impact both parties’ strategic positions.

As a good partner, the health system needs to understand if its contracted emergency department (ED) group is seeking to grow geographically, add new locations in its existing service area, expand into urgent care, or diversify into hospital medicine. Likewise, medical groups should seek to understand the priorities of the health system and identify opportunities to be rewarded for advancing the health system’s agenda—either through incentive bonuses or being rewarded additional contracts.

Consolidating contracts also helps health systems ensure coverage at facilities that providers find less desirable to cover. If you’re having trouble getting ED coverage at your rural critical access hospital, tell the group with the contract at your flagship facility to figure out how to cover the critical access hospital if they want to keep the contract.

Standardizing terms and provisions of PSAs doesn’t just mean getting all the legal mumbo jumbo consistent across contracts, although there is substantial value in that. It also means documenting expectations related to participation in quality, cost, and efficiency initiatives; clinical performance measurement and reporting; revenue cycle performance; participation in managed care contracting; and other aspects of the arrangement that foster collaboration and a level of interdependence that more closely ties the medical group to the health system.

Paying for Performance

In general, health systems tie far too little compensation to performance in their contracts for hospital-based services. Hospital-based medical groups have a tremendous impact on financial, quality, and patient satisfaction outcomes of hospitals. Who impacts the efficiency of your ORs or shortens the stays in your PACU more than anesthesiologists? How could your hospitalists help reduce length of stay and preventable readmissions? How much can your intensivists save the hospital by reducing ICU utilization, length of stay, and adverse events (e.g., ventilator-associated events, catheter-associated urinary-tract infections, central line–associated blood infections)? Health systems should establish performance expectations for hospital-based services, reward improvement, and tie a meaningful portion of compensation to performance.

Inclusion of key performance indicators (KPIs) in contracts for hospital-based services demonstrates to the Joint Commission that a health system is meeting the standard for ensuring the care, treatment, and services provided through contractual arrangements are performed safely and effectively. When choosing KPIs on which to base a portion of compensation to a medical group, select metrics that are meaningful, actionable, and credible. Although conditions at some facilities may provide reason to base compensation on some site-specific metrics, most metrics should be used across the health system. Performance should be monitored across facilities relative to baseline (previous performance) and against industry benchmarks.

Tiered performance incentive models frequently work well to promote alignment and encourage continuous improvement. Under a tiered approach, the health system rewards the medical group different amounts depending on performance. For example, the health system could provide a maximum bonus for reaching a stretch goal, a smaller bonus for reaching a minimum threshold, and no bonus for performance worse than the threshold. In most cases, improvement from baseline should be required for any bonus payment, but maintaining exceptional performance may be reason for providing incentive compensation on rare occasion.

Here’s a math problem for you. Assume your health system is contracting with a hospitalist group for services that should cost the group $10 million in wages and benefits for its providers. You estimate the group collects $8 million in excess of its billing and other overhead costs, so you agree to pay the group a $2 million subsidy. How much of the $2 million stipend should you tie to performance incentives if you want 20% of physician compensation to be incentive-based? The answer is all of it, meaning $2 million. However, many organizations would only place 20% of the $2 million subsidy, or $400,000, at risk. From the medical group’s perspective, $400,000 is only 4% of its potential income—not a big incentive to bend over backward to meet performance expectations. Instead, consider providing an incentive compensation package that could result in a total income to the group much greater than $10 million if performance improves but also put the group at risk of earning much less than $10 million if performance does not improve.

A Roadmap for Improvement

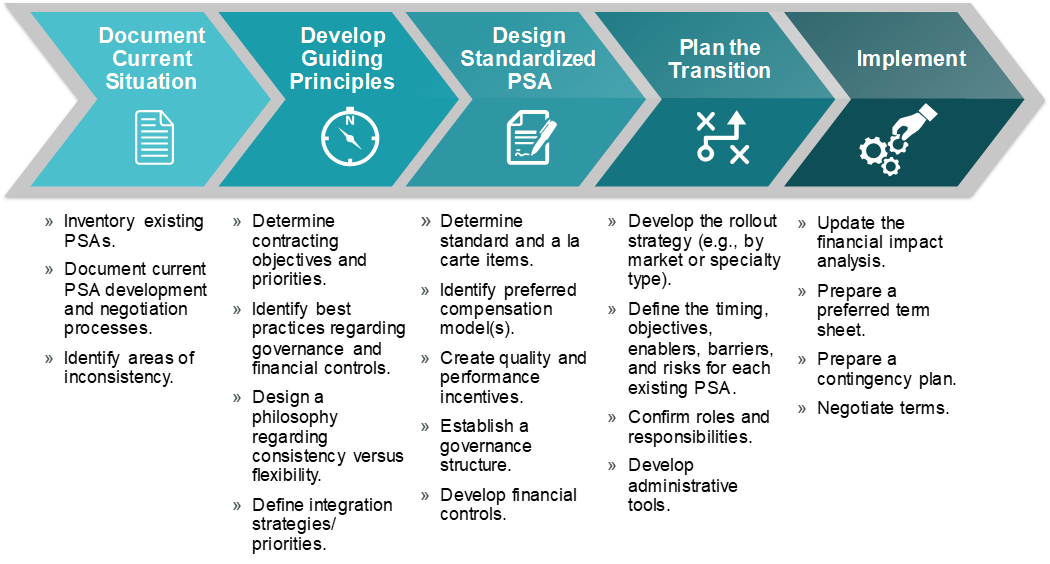

Health systems work hard to implement operational improvements to reduce their costs and improve care. But they cannot do it alone. Collaborating and aligning incentives with medical groups that substantially impact the hospital’s performance is needed to make lasting improvements. Figure 1 summarizes five steps to transition from fragmented and loosely managed hospital-based PSAs to consistent, goal-oriented, and integrated PSAs.

Figure 1: Approach to Optimize PSAs

Through this approach, a health system can optimize hospital-based physician services by implementing preferred staffing and coverage models, regionalizing and standardizing PSA management, and linking payment to medical groups with enhanced performance.