In the late 1990’s the term “integration,” largely associated with hospital ownership of primary care practices, fell on hard times, being viewed as a failed strategy by many. Hospital-owned medical practices were losing big money. Management teams and consultants alike removed words like "integrated delivery system," "group practice without walls," and "MSO" from our vocabularies and we headed off to find the next "silver bullet" to save the day! Some groups of hospital-owned practices were abandoned. Some hospital-owned practices were returned to the employed physicians (it was rumored in some instances for substantially less than the hospital's initial investment). Other hospitals capital-starved their physician networks, losing the best performing employed physicians in the process. Still others dramatically cut their operating losses by terminating physician employment contracts and closing locations.

Was physician employment a failed hospital strategy? Of course not! It was failed implementation. Hospitals that remained in the business and focused on learning the rules for success in owning and operating medical practices soon began stealing market share from their less astute competitors. By late 2002, consultants were again receiving telephone calls from hospitals and health systems in competitive markets indicating that since divesting of or "pruning" their networks of employed primary care physicians they had lost market share. About the same time, other hospitals and health systems began employing specialists, particularly invasive specialists, to develop or protect service lines. Today, it is fair to say that physician employment by hospitals has reached "feeding frenzy" proportions in several competitive markets around the country. The fact that many new physicians are seeking an employment option as they leave their training programs has fueled this latest round of employment activity. Moreover, as regulatory challenges to traditional equity joint ventures between hospitals and physicians increase, employment often provides an attractive alternative with less regulatory complexity.

The strategic power of the physician employment model for hospitals is significant. Those hospital leaders who fail to pay attention to the employment of physicians in their primary and secondary markets find that they are losing market share to competitors. Increasingly, those hospitals that employ large numbers of primary care physicians are contractually obligating those physicians to 'refer domestic" (with a few obvious exceptions and consistent with regulatory requirements, such as availability of services and patient choice). Others are taking a less draconian approach and educating their employed physicians about the fact that capital is generated in the hospital to support the integrated model, including those primary care practices. Their employed physicians understand that every dollar flowing to a competing hospital, either directly or indirectly is lost forever. These approaches are working, shifting market share away from even their most venerable hospital competitors. These significant strategic consequences involve what we call "Physician Integration Economics."

Physician Integration Economics

Physician Integration Economics defines how market share is captured and retained in primary care practices, is referred to specialists, who refer to facilities. It is this flow of market share that allows both revenue and capital to be generated to feed the entire community healthcare system. Smart specialty physicians and wise hospital executives understand that market share and market potential for both specialists and hospitals is a function of establishing and maintaining a strong relationship with primary care physicians, each of whom may capture, and refer when medically appropriate, 2,000 to 5,000 lives. [1]

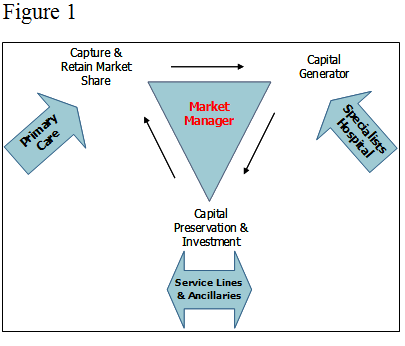

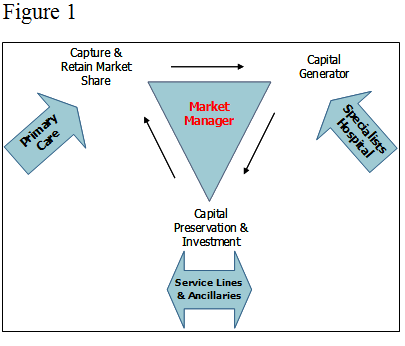

Figure 1 illustrates the Physician Integration Economics process. Market share is captured and retained in primary care practices, where long term relationships are built and revenue is generated for those practices. That market share is referred to both invasive and non-invasive specialists when patients require specialty services, and revenue is generated for those practices. A percentage of patients will require hospitalization and may be referred directly by primary care physicians or indirectly through specialists, where hospital revenue is generated, some of which becomes capital for future spending. Private medical practices generally do not retain earnings for capital spending. Instead, they borrow their capital. Only hospitals amass large amounts of capital through current earnings, by issuing bonds or through the public market.

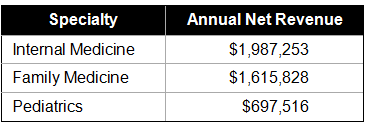

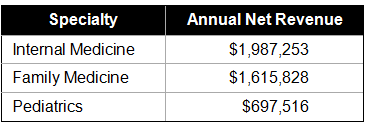

The financial value of physician utilization of hospital services has been the subject of debate for years. A recent survey conducted by Merritt, Hawkins & Associates asked hospital CFOs to provide the average inpatient and outpatient net revenue by several specialties through their direct referrals. The following table includes values provided for direct primary care referrals only. No indirect referrals to specialists were included.

The value of specialty physician net revenue ranged from a high of $2,662,600 for invasive cardiologists to a low of $557,916 for neurologists. The average for all specialty physicians (including OB/GYN) was $1,509,910 in 2007. [2]

While hospitals cannot legally pay physicians for referrals, the value of physician referrals and utilization of the hospital is clear. What is also clear is that value is decreasing since the last Merritt, Hawkins & Associates survey in 2004, when the average specialty net revenue was $1,885,773. [3] This phenomenon may be a function of changes in technology, changing reimbursement, competing physician-owned diagnostic and ambulatory surgery facilities, or other factors. Regardless, the trend further illustrates the importance of understanding and managing where market share is captured/retained and how it migrates through the system generating both revenue and capital.

Hospital administrator or market manager ?

Figure 1 also introduces the role of "market manager." A market manager has two key responsibilities in today's competitive environments. First, he or she must make certain that physicians want to use the hospital that the referral process proceeds unimpeded to ensure that market share can flow to the capital generating engine — the hospital. Second, the market manager must reinvest capital in the entire physician/hospital integrated system to ensure its viability and sustainability over the long term. The most likely market manager is the hospital chief executive because he or she has (at least potentially) the greatest influence on strengthening the physician integration model, on potential referral patterns, and on capital expenditures.

Successful market managers do not view themselves as hospital administrators. In fact, they delegate most hospital operations to competent lieutenants. Market managers develop and manage relationships to achieve the integrated system's strategic objectives. They are engaged in ensuring the success of affiliated primary care physicians and specialty physicians, as well as the hospital's service lines. Even if the hospital owns primary care and specialty practices, the market manager is personally involved in managing relationships with these critical "internal" customers as well as private practice physicians. Market managers are held accountable by boards or system leaders for their activities outside the hospital walls, as well as for hospital performance. The selection of Market Managers is driven by these expanded responsibilities. The measurement of their performance and the associated rewards are based on that same broad strategic scope.

Relationship management

Market managers realize that they cannot leave physician referral relationships to chance. They, and the relationship management teams they create, are critically aware of the two fundamental relationship management tenets: [4]

"Referrals follow relationships"

and,

"All relationships atrophy over time"

They must ensure that their hospital is the "Hospital of Choice" for patients and physicians alike and that their affiliated specialists are the "Specialists of Choice." [5] Further, they must affiliate in legally permissible ways with primary care physicians in the right geographic locations to garner the target patient population they seek. Then they must proactively manage relationships all along the referral chain to ensure that barriers are reduced or eliminated. Such relationship management consists of the following steps: [6]

The potential results

Relationship management under the direction of a dedicated market manager can yield huge potential returns on invested time and money. The principles that support paying attention to the issues faced by our affiliated physicians, be they employees or not, date back to the Hawthorne studies conducted by Elton Mayo in the 1920s and 1930s. [7] A few contemporary examples validate the market manager concept.

We earlier referenced the hospital CEO/market manager who paid special attention to the medical staff lounge. When this CEO arrived at her newly assigned hospital (part of a large health system) in the South, the facility was having trouble meeting payroll. The hospital was facing aggressive competitors, a depressed medical staff and limited capital. Fortunately, the medical staff included a number of dedicated primary care physicians who held more than adequate market share to support the hospital and its affiliated specialists. Among several performance improvement initiatives, the new CEO conducted a portfolio analysis to determine which service lines should receive her initial focus. She used an employment model to selectively "partner" with specialists supporting those service lines. With the help of those specialty leaders, service lines were strengthened to better meet the needs of referring physicians and their patients. She also began to remodel the medical staff lounge, even including plans for the employment of a concierge to assist her visiting physician customers (some of whom were now employed). Many individuals were skeptical of the potential impact. The results, however, convinced even those who were most skeptical. Within months, hospital performance had improved substantially and over the next few years bottom line profits rose 485 percent. These results placed her hospital among the top capital generators in the health system.

A second hospital CEO/market manager took over a troubled hospital in a medium-sized community. He realized that the hospital would need a lot of his personal attention, particularly early on in the turnaround. The sole community provider had larger competitors 45 minutes to the east and to the west. Outmigration to the larger communities for medical services was common. Among the strategies employed by this market manager was the recruitment of key physician specialists to bolster the services available in the hospital. A second critical strategy included hiring a consultant to help establish a physician relationship management process. Since the CEO was not always available, a skilled sales executive was hired and trained to help this Market Manager connect with some 200 potential referring physicians located around the region in more than 100 practices. Nine "sales routes" were established ensuring that all physicians were visited in their offices at least quarterly. Certain targeted physicians, identified by the hospital CEO were visited every four to six weeks. Despite the time it took to recruit new specialty physicians to the area, the relationship management program had had a significant effect. Even during the first year, inpatient admissions rose 3 percent, adding 308 admissions over the prior fiscal year, to contribute to fixed costs. Outpatient admissions rose 5 percent adding 1,396 cases to the total. Much of this increase occurred before new services were added, by simply alerting referring physicians to currently available services and asking for their business. During the second year, inpatient admissions increased by 762, or another 7 percent. Outpatient admissions grew 12 percent or 3,324 more cases than the first year.

Third, a health system built a new hospital in a highly competitive growing area of the marketplace. Competitors were already established, as were specialty and hospital referral patterns. The new hospital was part of a local system that owned several primary care practices, but only a few were in the new hospital's primary service area. The newly assigned hospital CEO recognized her role as a market manager. She also hired a full-time liaison with experience in medical practice management, physician recruitment and hospital services. The CEO and liaison worked as a team to develop a medical staff and to attract referrals from existing physicians by informing physicians about service availability and service quality at the new facility. They spent time inviting physicians to the new facility and conducting numerous tours. They also spent time in the offices of potential physician "partners" to discuss the services they needed and to improve hospital performance. The first year of operations, inpatient admissions were slightly over 4,800. During the second year of operations, inpatient admissions increased 50 percent, followed by another 10 percent increase the third fiscal year. Outpatient admissions during the first year were slightly over 2,400. Outpatient cases more than doubled during the second year and increased another 4 percent the third year, again, despite heavy competition from established competitors and despite previously established referral patterns.

Summary

Simply placing physician practices and hospitals in the same legal structure and on the same organization chart does not result in integration. Successful integration requires executives and physicians who understand and develop strategies based on physician integration economics. Successful integration requires a market manager, usually the hospital CEO, who understands the importance of developing and maintaining referral chains by investing capital in improving primary care access, responsive specialty services and high quality hospital service lines. Successful integration requires the full time and attention of the market manager and his or her team, not leaving any relationships to chance. Successful integration has a demonstrable return on investment and provides for strategic sustainability over the long term.

Footnotes:

[1] Halley M. D. 2007. The Primary Care—Market Share Connection: How Hospitals Achieve Competitive Advantage. Chicago: Health Administration Press, xi.

[2] Merritt, Hawkins & Associates. 2008. “2007 Physician Inpatient/Outpatient Revenue Survey. Available http://www.merritthawkins.com/pdf/2007_Physician_Inpatient_Outpatient_Revenue_Survey.pdf.

[3] Ibid., 8.

[4] Halley, M.D. 2007. The Primary Care—Market Share Connection: How Hospitals Achieve Competitive Advantage. Chicago: Health Administration Press, 120-121.

[5] Halley, M.D. 2006. Specialist of Choice Practice Evaluation. The Halley Consulting Group, LLC. Available http://www.halleyconsulting.com.

[6] Halley, M.D. 2007. The Primary Care—Market Share Connection: How Hospitals Achieve Competitive Advantage. Chicago: Health Administration Press, 122-124.

[7]Hampton, D. 1977. Contemporary Management. New York:NY. McGraw-Hill. p. 15-19.

Marc D. Halley, MBA, is President and CEO of The Halley Consulting Group, LLC., Westerville, Ohio.

Peg Holtman is President and CEO of Healthcare Marketing Systems, Inc., New Albany, Indiana.

Anthony D. Shaffer, Esquire is a Senior Attorney with Squire, Sanders & Dempsey, LLP., Columbus, Ohio.

Was physician employment a failed hospital strategy? Of course not! It was failed implementation. Hospitals that remained in the business and focused on learning the rules for success in owning and operating medical practices soon began stealing market share from their less astute competitors. By late 2002, consultants were again receiving telephone calls from hospitals and health systems in competitive markets indicating that since divesting of or "pruning" their networks of employed primary care physicians they had lost market share. About the same time, other hospitals and health systems began employing specialists, particularly invasive specialists, to develop or protect service lines. Today, it is fair to say that physician employment by hospitals has reached "feeding frenzy" proportions in several competitive markets around the country. The fact that many new physicians are seeking an employment option as they leave their training programs has fueled this latest round of employment activity. Moreover, as regulatory challenges to traditional equity joint ventures between hospitals and physicians increase, employment often provides an attractive alternative with less regulatory complexity.

The strategic power of the physician employment model for hospitals is significant. Those hospital leaders who fail to pay attention to the employment of physicians in their primary and secondary markets find that they are losing market share to competitors. Increasingly, those hospitals that employ large numbers of primary care physicians are contractually obligating those physicians to 'refer domestic" (with a few obvious exceptions and consistent with regulatory requirements, such as availability of services and patient choice). Others are taking a less draconian approach and educating their employed physicians about the fact that capital is generated in the hospital to support the integrated model, including those primary care practices. Their employed physicians understand that every dollar flowing to a competing hospital, either directly or indirectly is lost forever. These approaches are working, shifting market share away from even their most venerable hospital competitors. These significant strategic consequences involve what we call "Physician Integration Economics."

Physician Integration Economics

Physician Integration Economics defines how market share is captured and retained in primary care practices, is referred to specialists, who refer to facilities. It is this flow of market share that allows both revenue and capital to be generated to feed the entire community healthcare system. Smart specialty physicians and wise hospital executives understand that market share and market potential for both specialists and hospitals is a function of establishing and maintaining a strong relationship with primary care physicians, each of whom may capture, and refer when medically appropriate, 2,000 to 5,000 lives. [1]

Figure 1 illustrates the Physician Integration Economics process. Market share is captured and retained in primary care practices, where long term relationships are built and revenue is generated for those practices. That market share is referred to both invasive and non-invasive specialists when patients require specialty services, and revenue is generated for those practices. A percentage of patients will require hospitalization and may be referred directly by primary care physicians or indirectly through specialists, where hospital revenue is generated, some of which becomes capital for future spending. Private medical practices generally do not retain earnings for capital spending. Instead, they borrow their capital. Only hospitals amass large amounts of capital through current earnings, by issuing bonds or through the public market.

The financial value of physician utilization of hospital services has been the subject of debate for years. A recent survey conducted by Merritt, Hawkins & Associates asked hospital CFOs to provide the average inpatient and outpatient net revenue by several specialties through their direct referrals. The following table includes values provided for direct primary care referrals only. No indirect referrals to specialists were included.

The value of specialty physician net revenue ranged from a high of $2,662,600 for invasive cardiologists to a low of $557,916 for neurologists. The average for all specialty physicians (including OB/GYN) was $1,509,910 in 2007. [2]

While hospitals cannot legally pay physicians for referrals, the value of physician referrals and utilization of the hospital is clear. What is also clear is that value is decreasing since the last Merritt, Hawkins & Associates survey in 2004, when the average specialty net revenue was $1,885,773. [3] This phenomenon may be a function of changes in technology, changing reimbursement, competing physician-owned diagnostic and ambulatory surgery facilities, or other factors. Regardless, the trend further illustrates the importance of understanding and managing where market share is captured/retained and how it migrates through the system generating both revenue and capital.

Hospital administrator or market manager ?

Figure 1 also introduces the role of "market manager." A market manager has two key responsibilities in today's competitive environments. First, he or she must make certain that physicians want to use the hospital that the referral process proceeds unimpeded to ensure that market share can flow to the capital generating engine — the hospital. Second, the market manager must reinvest capital in the entire physician/hospital integrated system to ensure its viability and sustainability over the long term. The most likely market manager is the hospital chief executive because he or she has (at least potentially) the greatest influence on strengthening the physician integration model, on potential referral patterns, and on capital expenditures.

Successful market managers do not view themselves as hospital administrators. In fact, they delegate most hospital operations to competent lieutenants. Market managers develop and manage relationships to achieve the integrated system's strategic objectives. They are engaged in ensuring the success of affiliated primary care physicians and specialty physicians, as well as the hospital's service lines. Even if the hospital owns primary care and specialty practices, the market manager is personally involved in managing relationships with these critical "internal" customers as well as private practice physicians. Market managers are held accountable by boards or system leaders for their activities outside the hospital walls, as well as for hospital performance. The selection of Market Managers is driven by these expanded responsibilities. The measurement of their performance and the associated rewards are based on that same broad strategic scope.

Relationship management

Market managers realize that they cannot leave physician referral relationships to chance. They, and the relationship management teams they create, are critically aware of the two fundamental relationship management tenets: [4]

"Referrals follow relationships"

and,

"All relationships atrophy over time"

They must ensure that their hospital is the "Hospital of Choice" for patients and physicians alike and that their affiliated specialists are the "Specialists of Choice." [5] Further, they must affiliate in legally permissible ways with primary care physicians in the right geographic locations to garner the target patient population they seek. Then they must proactively manage relationships all along the referral chain to ensure that barriers are reduced or eliminated. Such relationship management consists of the following steps: [6]

- Understand the medical practice context: Market managers must develop a clear understanding of the challenges of medical practice and how well their affiliated and owned medical practices are performing. Most physicians certainly understand, but may not be overly interested in the hospital's mission. If they are in private practice, they are worried about meeting the next payroll. If they are employed by the hospital, they are worried about the quality of their practice and home life. They are going to be concerned about how the hospital can help them be more successful through improved scheduling of ancillary tests, operating rooms, etc. A smart market manager will focus on these issues first.

- Customer contact: Market managers understand that they can and should associate with their specialists who attend the hospital. They spend time each day in the medical staff lounge, which is a safe haven for those specialists who still use the hospital workshop. One market manager we know developed a beautiful and comfortable facility for attending physicians. The lounge design included the office of the chief medical officer who is readily accessible with no meetings during peak medical staff lounge hours. The market manager personally visits the lounge often, a critically simple, but frequently ignored tactic. Too many hospital administrators don't take the time to be present because they have too many early morning hospital meetings.

Market managers realize that most of their affiliated primary care physicians never visit the hospital. This challenge is addressed by the hospital CEO and other competent team members visiting primary care physicians on their turf. They have specific physician targets and go with a specific agenda that is heavily biased toward understanding the physicians; world and the challenges they face in providing quality care in today’s environment. Some Market Managers use one or more sales professionals or liaisons to help manage the process and to leverage the market manager, but wise CEOs are personally involved in key visits every week.

- Listen for oppportunity: Market managers and their liaisons ask key questions about the practice specialty, about access to specialists, and about the hospital's performance. Some of the answers may be difficult to hear, but need to be understood, whether they are based in reality or not! Perception is reality and must be heard and acknowledged if it is to be changed.

- Follow up: A "contact report" is written after each visit, documenting the highlights for discussion among the Market Manager and his/her relationship management team. Performance issues and other action items are identified on an action plan managed by the Market Manager. Hospital issues are addressed by hospital operating experts. Specialty physician issues are addressed by the market manager and the service line leaders.

- Feedback: Within thirty days of the visit, a thank you note and specific feedback are sent to the primary care physicians. A "no" answer is preferably delivered by the market manager face-to-face, or at least in a personal telephone call.

The potential results

Relationship management under the direction of a dedicated market manager can yield huge potential returns on invested time and money. The principles that support paying attention to the issues faced by our affiliated physicians, be they employees or not, date back to the Hawthorne studies conducted by Elton Mayo in the 1920s and 1930s. [7] A few contemporary examples validate the market manager concept.

We earlier referenced the hospital CEO/market manager who paid special attention to the medical staff lounge. When this CEO arrived at her newly assigned hospital (part of a large health system) in the South, the facility was having trouble meeting payroll. The hospital was facing aggressive competitors, a depressed medical staff and limited capital. Fortunately, the medical staff included a number of dedicated primary care physicians who held more than adequate market share to support the hospital and its affiliated specialists. Among several performance improvement initiatives, the new CEO conducted a portfolio analysis to determine which service lines should receive her initial focus. She used an employment model to selectively "partner" with specialists supporting those service lines. With the help of those specialty leaders, service lines were strengthened to better meet the needs of referring physicians and their patients. She also began to remodel the medical staff lounge, even including plans for the employment of a concierge to assist her visiting physician customers (some of whom were now employed). Many individuals were skeptical of the potential impact. The results, however, convinced even those who were most skeptical. Within months, hospital performance had improved substantially and over the next few years bottom line profits rose 485 percent. These results placed her hospital among the top capital generators in the health system.

A second hospital CEO/market manager took over a troubled hospital in a medium-sized community. He realized that the hospital would need a lot of his personal attention, particularly early on in the turnaround. The sole community provider had larger competitors 45 minutes to the east and to the west. Outmigration to the larger communities for medical services was common. Among the strategies employed by this market manager was the recruitment of key physician specialists to bolster the services available in the hospital. A second critical strategy included hiring a consultant to help establish a physician relationship management process. Since the CEO was not always available, a skilled sales executive was hired and trained to help this Market Manager connect with some 200 potential referring physicians located around the region in more than 100 practices. Nine "sales routes" were established ensuring that all physicians were visited in their offices at least quarterly. Certain targeted physicians, identified by the hospital CEO were visited every four to six weeks. Despite the time it took to recruit new specialty physicians to the area, the relationship management program had had a significant effect. Even during the first year, inpatient admissions rose 3 percent, adding 308 admissions over the prior fiscal year, to contribute to fixed costs. Outpatient admissions rose 5 percent adding 1,396 cases to the total. Much of this increase occurred before new services were added, by simply alerting referring physicians to currently available services and asking for their business. During the second year, inpatient admissions increased by 762, or another 7 percent. Outpatient admissions grew 12 percent or 3,324 more cases than the first year.

Third, a health system built a new hospital in a highly competitive growing area of the marketplace. Competitors were already established, as were specialty and hospital referral patterns. The new hospital was part of a local system that owned several primary care practices, but only a few were in the new hospital's primary service area. The newly assigned hospital CEO recognized her role as a market manager. She also hired a full-time liaison with experience in medical practice management, physician recruitment and hospital services. The CEO and liaison worked as a team to develop a medical staff and to attract referrals from existing physicians by informing physicians about service availability and service quality at the new facility. They spent time inviting physicians to the new facility and conducting numerous tours. They also spent time in the offices of potential physician "partners" to discuss the services they needed and to improve hospital performance. The first year of operations, inpatient admissions were slightly over 4,800. During the second year of operations, inpatient admissions increased 50 percent, followed by another 10 percent increase the third fiscal year. Outpatient admissions during the first year were slightly over 2,400. Outpatient cases more than doubled during the second year and increased another 4 percent the third year, again, despite heavy competition from established competitors and despite previously established referral patterns.

Summary

Simply placing physician practices and hospitals in the same legal structure and on the same organization chart does not result in integration. Successful integration requires executives and physicians who understand and develop strategies based on physician integration economics. Successful integration requires a market manager, usually the hospital CEO, who understands the importance of developing and maintaining referral chains by investing capital in improving primary care access, responsive specialty services and high quality hospital service lines. Successful integration requires the full time and attention of the market manager and his or her team, not leaving any relationships to chance. Successful integration has a demonstrable return on investment and provides for strategic sustainability over the long term.

Footnotes:

[1] Halley M. D. 2007. The Primary Care—Market Share Connection: How Hospitals Achieve Competitive Advantage. Chicago: Health Administration Press, xi.

[2] Merritt, Hawkins & Associates. 2008. “2007 Physician Inpatient/Outpatient Revenue Survey. Available http://www.merritthawkins.com/pdf/2007_Physician_Inpatient_Outpatient_Revenue_Survey.pdf.

[3] Ibid., 8.

[4] Halley, M.D. 2007. The Primary Care—Market Share Connection: How Hospitals Achieve Competitive Advantage. Chicago: Health Administration Press, 120-121.

[5] Halley, M.D. 2006. Specialist of Choice Practice Evaluation. The Halley Consulting Group, LLC. Available http://www.halleyconsulting.com.

[6] Halley, M.D. 2007. The Primary Care—Market Share Connection: How Hospitals Achieve Competitive Advantage. Chicago: Health Administration Press, 122-124.

[7]Hampton, D. 1977. Contemporary Management. New York:NY. McGraw-Hill. p. 15-19.

Marc D. Halley, MBA, is President and CEO of The Halley Consulting Group, LLC., Westerville, Ohio.

Peg Holtman is President and CEO of Healthcare Marketing Systems, Inc., New Albany, Indiana.

Anthony D. Shaffer, Esquire is a Senior Attorney with Squire, Sanders & Dempsey, LLP., Columbus, Ohio.