Most hospitals in recent years have focused needed attention on preventing surgical site infections. Properly timed antibiotics, skin antisepsis, appropriate hair removal, hand hygiene and other measures are now stressed as important to reducing SSI rates. But one critical dimension of infection safety has received comparatively little attention — the sterile processing department.

The following content is sponsored by Surgical Directions.

Most hospitals in recent years have focused needed attention on preventing surgical site infections. Properly timed antibiotics, skin antisepsis, appropriate hair removal, hand hygiene and other measures are now stressed as important to reducing SSI rates. But one critical dimension of infection safety has received comparatively little attention — the sterile processing department.

SPD is the first link in the infection-prevention chain. Improperly cleaned, disinfected and sterilized instruments can introduce pathogens into the OR, increasing the risk of an SSI. Like all systems, sterile processing is not perfect. But the major problem is lack of awareness. Clinical and executive leaders often fail to give sterile processing the same attention they devote to other safety-critical processes.

We have worked with hospital ORs nationwide to improve efficiency and safety. In the majority of organizations, problems and weaknesses in SPD are under-recognized. Based on our experience, patients face an increased risk of SSI because of seven common problems:

Inappropriate use of "flash" sterilization. According to the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, immediate-use sterilization should be employed only for emergencies. For example, if an instrument is dropped during surgery and a sterile replacement is not available, rapid sterilization through an immediate-use process is appropriate. One problem is that immediate-use sterilization is a complex, multi-step process with ample opportunity for lapse and error. In addition, SPD managers and staff in many hospitals have become complacent, lowering the bar of “emergency” use. As SPD units increase their use of this difficult process, the risk of delivering inadequately sterilized instruments to the OR increases.

Trays exceeding weight limits. Most sterilization systems specify that instrument trays should not exceed 25 pounds, including the weight of the tray and any containers. But there is widespread confusion about this requirement. Some managers see tray weight restrictions as a worker safety issue. In fact, sterilizing equipment is not as effective for heavier trays. Failure to observe tray weight limitations can result in inadequate processing and increased risk of patient infection.

Moisture and condensation in instrument trays. Instrument trays that are not allowed to dry completely after sterilization present another common risk. The problem is that wet spots on the tray wrapper can allow bacteria to wick through to the contents of the tray. Moisture can also result from condensation when processed trays are stored in improper temperature and humidity conditions. Wet trays should be re-processed, but they often make it to the OR for surgery.

Ineffectively processed endoscopes. Flexible endoscopes present unique challenges for central sterile. Staff must completely remove bio burden from lumens and channels using appropriately sized brushes. Endoscope lumens are typically too small to be adequately sterilized by steam, so alternative methods must be used. The instruments must also be thoroughly inspected for damage, including leak testing. The difficulty and complexity of the entire process increases the risk that pathogens will survive their visit to SPD. Problems with flexible endoscopes are particularly common in colorectal surgery.

Inadequate and poorly maintained equipment. Common equipment problems include rust and corrosion in and around washer sterilizers and steam sterilizers. Some hospital SPDs do not have a cart washer, forcing staff to wash cart units by hand. This puts staff at risk and also increases the chance of improper decontamination. Many SPDs lack proper lighting and magnification equipment, increasing the risk of inadequate inspection. Poor maintenance of surgical instruments also compromises the sterilization process. Typical problems include pitting, corrosion and worn threads on items that require disassembly.

Poor control of vendor trays. Many implant vendor representatives bring loaner trays to the OR for use during surgery, frequently for orthopedic and spine procedures. The problem is that vendors often fail to arrive in time to allow adequate processing of the instrument tray. Some hospitals have written policies about the advance time needed to process loaner trays, but staff may choose to overlook the policy and process the tray using flash sterilization.

Inadequate support from OR staff. SPD units are not exclusively responsible for sterile process failures. During procedure setup, OR techs may fail to adequately inspect instrument tray wrappers and canister filters or check indicator strips to verify processing. On the back end, OR staff often fail to apply enzymatic cleaner before sending instruments back to SPD. This increases the chance of bio burden drying on to the instrumentation, making it harder to ensure proper decontamination for the next use.

Five strategies for improving SPD

Given the risks of SSI, improving sterile processing should be seen as a priority issue. The following five interventions can have a strong positive impact on SPD operations, efficiency and outcomes.

1. Monitor sterile processing key performance indicators

As the old saying goes, "If you can't measure it, you can't manage it." Yet most hospitals track very little data for sterile processing. To begin improving SPD, establish performance measures for sterile processing operations and outcomes. Key metrics can include immediate-use sterilization usage rates, damaged tray rates (including tracking of wet trays) and preventive maintenance plan adherence rates.

Include sterile processing key performance indicators in operational dashboard reports used by perioperative leadership. Share performance targets with SPD staff, and use metrics as a focus point for process education and change.

2. Invest in SPD staff development

Staff education is inconsistent in many SPD units. Most SPD staff learn on the job, as did their trainers. In this environment, incorrect practices are often perpetuated. To develop a high-performing unit, hospitals need to invest in advanced training for SPD staff.

Encourage staff to seek certification from a national or international organization. Reimburse staff for course and exam fees. In addition, establish SPD in-service days for ongoing refreshers, best practice updates and performance improvement.

3. Streamline SPD workflow

In many SPDs, staff and material follow a “spaghetti diagram” path from decontamination through storage. Chaotic workflows increase the risk of process lapses and can help create a sense of rush that weakens safety.

Top-performing SPDs use Lean analysis to streamline workflows. Engage a trained Lean expert to analyze your department, create a value stream map and apply proven process redesign strategies. Smoother workflows in SPD will help ensure optimal quality and safety.

4. Hold OR staff accountable

Most OR techs and nurses understand their role in sterile processing, but complacency can reduce compliance. OR supervisors can address this problem by incorporating sterile processing issues into clinical rounds. Do staff adequately inspect instrument trays during setup? Do staff adequately process used instruments during breakdown? In addition, OR educators should cover instrument care and handling during in-service sessions.

5. Update SPD equipment

Given the state of equipment in many SPD units, many hospitals need to commit to a significant investment in SPD upgrades. A wide array of systems, technologies and options are available. Hospital leaders should collaborate with SPD management, OR leadership and infection control to create an effective and manageable upgrade strategy. Then, work with finance to develop a three- to five- year capital spending plan to optimize SPD equipment.

Leadership solution needed

The prerequisite to all these strategies is strong commitment from hospital executives. The problem is that SPD is "below the radar" of most hospital executives. As a result, SPD often fails to get the leadership attention and resources that hospital departments need to achieve high performance.

In our experience, hospital CEOs are often surprised to learn about problems and weaknesses in their sterile processing department. The good news is that once hospital leaders understand the issues, most are eager to make needed changes. Two points are key to communicating with executives:

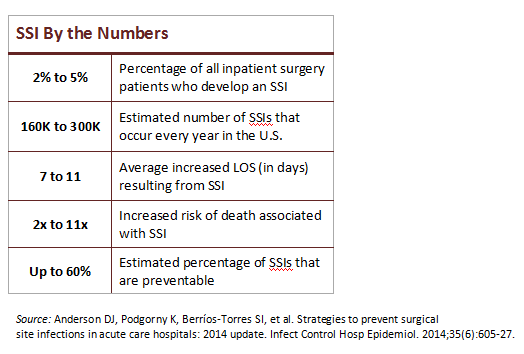

The patient safety issue. SSIs are a major problem for U.S. hospitals (see sidebar). They affect a significant number of surgery patients, impairing recovery and leading to long-term disability. Most hospital ORs have made big process changes to improve intraoperative safety, but these gains are vulnerable to weaknesses in SPD.

The financial issue. CMS will begin penalizing hospitals for high rates of SSIs (and other healthcare-acquired conditions) in 2015. In addition, SSIs dramatically increase the risk of re-hospitalization, putting hospitals at greater risk of readmission penalties. As payment evolves toward full value-based care through bundled payment and other mechanisms, high SSI rates could undercut profitability.

These safety and financial issues together create a compelling case for prompt action to improve SPD performance. Engaging hospital leaders in this goal is key to creating strong end-to-end processes for preventing SSIs and ensuring optimal patient safety and quality.

Alecia Torrance, RN, BS, MBA, CNOR, is senior vice president of clinical operations, and Barbara McClenathan, RN, BSN, MBA-HCM, CNOR, is senior nurse executive at Surgical Directions, a perioperative consulting firm that helps hospital ORs improve efficiency, financial performance, clinical outcomes, and patient and staff satisfaction. They can be reached at (312) 870-5600.