The fee-for-service model that has allowed hospital-dominated health systems to use capital investments and inpatient market share to garner financial returns is quickly shifting towards a population health and risk-sharing reimbursement model. There are multiple reasons for this shift including the economic recession, healthcare reform and technological advancements in both information and medical technology. Two key implications of this shift to a risk-sharing reimbursement model are the declining strength and relevance of the hospital-dominated health systems in leading the healthcare delivery model in their markets.

Consider a few recent events. First, Congress negotiated again to avert a scheduled 26.5 percent cut in Medicare payments to physicians but cut hospital reimbursement to make up more than half of the lost savings (an estimated $25.1 billion dollars). Moreover, additional cuts can be expected in the upcoming budget negotiations, including a 2 percent cut from Medicare if the sequester cuts do indeed take place.

Second, insurers are rapidly moving into the provider businesses. Insurers are outright purchasing large physician organizations.[1] using risk sharing contracts to partner with physicians, or a combination of both. For example, Humana sees a "compelling rationale for greater role in primary care." Some of the reasons listed include: to credibly influence primary care physicians and drive efficient medical spend, to control costs and to enhance the development of risk relationships.[2] The anticipated result by most insurers is cost reductions, with many of the dollars being pulled out of the traditional hospital businesses. In fact, through the narrowing of networks to preferred physician groups, commercial insurers are predicting the ability to reduce costs by as much as 20 percent compared to traditional plans.[3]

Third, the continued growth and acceptance of information technology has opened the possibility for insurers and employers to own a portion of the primary care delivery network through the use of online diagnosis and treatment services. Examples include VirtuWell, owned by the integrated system Health Partners in Minnesota, and Teledoc, which is partnering with Highmark in Pennsylvania, Aetna in Alaska and Blue Shield of California, among others, to provide care for patients online.

In markets where these events have occurred, hospital-dominated health systems have been scrambling to respond as their market influence has dramatically dissipated and the future relevance of the system is being threatened.

Building a primary care base is an important strategy for health systems to combat these competitive trends. As a result, the market has seen a resurgence of hospitals and health systems employing primary care physician practices with as many as 40 percent of all primary care physicians now employed by health systems.[4] However, simply buying primary care physician practices is a brute-force tactic for remaining relevant that will leave health systems expending larger and larger resources for smaller impact and ignores the ways populations' access primary care. Instead, successful systems will develop a multiple channel primary care access strategy that address the populations' specific needs for long-term relationships with clinicians as well as on-demand access to urgent and convenient clinical diagnosis, decision making and treatment.

Populations access primary care in two major channels with multiple sub-channels:

1. Scheduled primary care access channels:

- Physician-staffed primary care clinics

- Nurse practitioner-staffed primary care clinics

2. On-Demand primary care access channels:

- Emergency room

- Urgent care

- Retail clinic

- Online care

Scheduled access channels

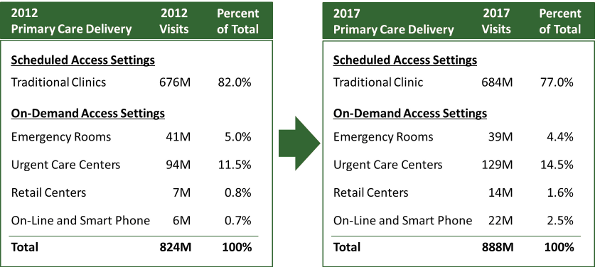

Traditional health system approaches to improving primary care access by employing primary care physicians and moving them into a specific market is an example of a scheduled access channel. A 2013 study by Health System Advisors shows scheduled, primary care clinic visits account for some 82 percent of all primary care visits in the U.S. today. And, while the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act provides means for increasing the reimbursement for primary care providers, the scheduled access channel is projected to play a smaller role in the future as the populations find more suitable channels for their needs.[5] In fact, even as health systems are growing their physician employment tactics, HSA projects that by 2017 the scheduled access channel will account for only 77 percent of the primary care visits in the U.S.

Physician-staffed primary care clinics. Physician-staffed primary care clinics form the backbone for the primary care access in the United States today. However, while they form the backbone of the delivery model, the channel has declined in some markets as much as 9 percent in 2010 and 2011[6] with insured patient visits declining even further at 17 percent.[7] Moreover, the need for primary care physicians is increasing at a time when the number of new primary care graduates is declining. The projected result is a shortage of 91,200 primary care physicians by 2020 if the current model is continued.[8]

In the physician-staffed primary care clinics, there is increased attention being given to team-based medicine to improve the efficiency of the channel. This includes additional use of nurse practitioners, physician assistants and other care-givers as well as the growth of formalized team-based models such as Patient Centered Medical Homes.[9]

Numerous studies have shown the positive impact of team-based care models with standardized PCMH models being the most studied. In short, studies show PCMH models improve patients' health with subsequent reductions in emergency room visits, hospital admissions and disease progression, though it is not without challenge. The most notable challenges are the need for a different reimbursement model than traditional fee-for-service, practice scale to create critical mass of teams and high-quality information systems.[10]

Nurse practitioner-staffed primary care clinics. Nurse practitioners have supported physician-staff primary care clinics in larger settings for years. What is newer is the increasing acceptance of primary care clinics staffed almost exclusively by nurse practitioners or in ratios of three or four nurse practitioners to one physician. Historical concerns about quality of care with nurse practitioner clinics have been proven unfounded. In fact, several studies show nurse practitioner clinics both reduce costs and deliver the same outcomes as primary care physician clinics.[11] Moreover, for managing populations with chronic diseases, larger clinic settings have created subspecialized teams around chronic diseases such as diabetes, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and for those with unhealthy lifestyles such as obesity and smoking. State-by-state regulations vary significantly; however, twelve states allow for fully independent nurse practitioner practices.[12]

Successful health systems will incorporate scheduled primary care access channels into their strategies, but will do so using non-physician providers and utilizing proven better clinical care models such as PCMHs along with their physician employment tactics.

On-Demand access channels

The most exciting changes happening in primary care today are in the on-demand access channels. Technology, medical decision making and population expectations have combined to create new, more efficient, cost effective and convenient.

The on-demand access channel is defined by the ability for populations to access care whenever they want it (on demand) rather than having to schedule time around a provider’s restrictions. There are five delivery models for the on-demand access channel.

Emergency room. The ER has long been an on-demand portal for populations to access healthcare. Intended to be only for those populations that are emergently ill or injured, it has, for many of the uninsured and indigent, been a major source of primary care access. Nationally, of the some 136 million ER visits, at least 20 percent, and perhaps as high as 60 percent, of the visits are primary care in nature.[13] [14] As a result, the ER represents a significant primary care channel, albeit one that is not structured to provide the care efficiently, cost effectively or conveniently in most cases.

Urgent care. An important strategy to off-load the crowded ERs, urgent care has seen resurgence over the past several years as physician clinics, health systems, and insurers try to capture populations that want on-demand access to primary care.

In 2012 the urgent care channel represented approximately 11.5 percent of the primary care delivery system in the U.S. The urgent care delivery models fall into two subsets: after hours care, typically provided in primary care physician (and more recently in orthopedic and other specialty care) offices, and free-standing care. Free standing centers are typically scaled for 5,000 to 15,000 visits annually. An estimated 9,300 urgent care centers were in operation in 2012 with $12-14 billion in total revenue. This channel is experiencing continued strong growth. Having doubled over the past decade, urgent care volumes are expected to grow by 6-8 percent annually through 2017.[15]

Retail clinics. Modern retail clinics started in 2000 with the frustration of a parent trying to access primary care for his child when he needed the care without having to go to the emergency room. What started in 2000 is now a 600+ clinic national network of MinuteClinics inside CVS pharmacy stores.

After a slow start, retail clinics grew dramatically before stabilizing in 2009 at approximately 1,200 clinic sites. Since 2010, they have again begun to grow at a steady pace with nearly 1,500 clinics open at the end of 2012 seeing an estimated 7 million visits per year. These clinics are located inside grocery stores, drug stores and big box stores and fill a gap in basic coverage that might otherwise find its way to the emergency department. Typical retail clinics operate in existing retail space and charge an average $110 per visit.[16]

Future projections show this channel growing significantly with most retail clinic chains planning 10 percent or greater growth annually and one national chain projecting 50 percent growth in the coming 18 months.

Online care. Online healthcare delivery is a relatively recent innovation. It has branched out from the traditional telemedicine where providers share resources and knowledge with each other. Today, online healthcare has the broad goals of encompassing preventative, promotional, diagnostic and curative aspects of primary care. It enables consumers to have virtual office visits and physicians to perform virtual rounding, increasing access to care. Changing reimbursement environments are requiring more payors to reimburse for telemedicine in many states, though some payors are doing so without state mandates.

Online clinics such as Virtuwell, launched in by HealthPartners in Minnesota in 2010, have seen indications that it can improve the patient experience, aid in population health management and reduce costs. In a 2013 published study, HealthPartners reviewed over 180,000 cases and saw an average of $88 lower cost per episode over traditional physician clinics and a 98 percent customer satisfaction rate.[17] Other Minnesota providers have seen similar success which have benefited from less stringent telemedicine licensing restrictions than other states.[18]

Trends continue to grow on-demand access channels. At the macro level, the trends are clear. Patient visits are growing in the on-demand channels, while they stagnate or shrink in the scheduled clinic channels. Moreover, the patient demographics and payor sources vary significantly across channels. For instance, a study done a couple years ago showed adults age 25-29 were seven times more likely to use on-demand primary care channels than Medicare-aged adults 65+.[19]

While today some 82 percent of primary care is delivered in scheduled clinic settings, HSA expects the growth of on-demand models to dramatically increase the availability of primary care to the population. By 2017 we anticipate the on-demand portion of primary care to account for more than 23 percent of primary care access in the U.S. Moreover, the growth of on-demand channels shows the potential substitution effect of the on-demand channels for the more traditional primary care office models. However, this channel competition does not eliminate the need for health systems to build the primary care access models that their populations demand.

These trends do not signal the end of traditional primary care clinics. It does mean health systems that are using primary care access and growth strategies to remain relevant in their markets must think beyond primary care physician employment and incorporate the multiple channels of primary care when designing their primary care access strategy.

Jeff Heidenreich is a strategic analyst and Luke C. Peterson is a principal at Health System Advisors. They can be contacted at Jeff.Heidenreich@HealthSystemAdvisors.com or Luke.Peterson@HealthSystemAdvisors.com. Health System Advisors is a strategy consultancy whose mission is to advise leaders, advance organizations and transform the healthcare industry. For more information contact HSA at 877.776.3639 or www.HealthSystemAdvisors.com.

[1] https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-physician-relationships/unitedhealth-group-buys-2300-physicians-in-california.html

[2] Humana “Evolving Primary Care Channel Dynamics and Care Integration” Morgan Stanley Town Hall March, 2012

[3] Burns, J. “Narrow Networks Found To Yield Substantial Savings.” Managed Care February, 2012.

[4] Advisory Board survey quoted in the New York Times, “Same Doctor, Double the Cost”, 2012

[5] “Where Americans Get Acute Care: Increasingly, It’s Not at Their Doctor’s Office”. Pitts, Carrier, Rich, and Kellermann. Health Affairs 2010

[6] IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics, 2012

[7] Kaiser Family Foundation, November 2011

[8] Association of American Medical Colleges, 2011

[9] See www.NCQA.org for more information on PCMH

[10] Site study on practice scale if we get that published

[11] “Nurse Practitioners as an underutilized resource for health reform: Evidence-based demonstrations of cost-effectiveness” Bauer et al, Journal of American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 2010

[12] A state-by-state review can be found at www.healthsystemadvisors.com under the Thought Leadership pages

[13] Billings J, Parikh N, Mijanovich T. Issue brief: Emergency department use in New York City:

substitute for primary care? New York: The Commonwealth Fund;2000

[14] Medpac study of Medicare beneficiaries showed 60% of ER visits could be avoided with better primary care. “Population-Based Measures of Ambulatory Care Quality: Potentially Preventable Admissions and Emergency Department Visits” Sandownik et al, 2012

[15] IBIS World “Urgent Care Reports”, 2012

[16] “More healthcare in store”. Barr. ModernHealthcare.com. November 2012

[17] “HealthPartners’ Online Clinic For Simple Conditions Delivers Savings Of $88 Per Episode And High Patient Approval” Courneya, Palatto, and Gallagher, Health Affairs, 2013

[18] A state-by-state review can be found at www.healthsystemadvisors.com under the Thought Leadership pages

[19] “Pilot Study of Providing Online Care in the Primary Care Setting”, Adamson, Mayo Clinic Proc. 2010 August; 85(8): 704–710