In February 2013 a couple in suburban Chicago discovered that the leads from a cardiac defibrillator implanted in their 9-year-old daughter had been recalled by the manufacturer after widespread reports of failure. Neither the providers involved in her care nor the manufacturer had informed them of the recall.

"I was reading my email one day — a newsletter we get," the child's mother, Molly de Groh, told a local TV station. "I saw there had been a recalled device. I scrambled to look, got out [my daughter's] medical cards, went to the FDA website, and, lo and behold, it was her device. It was like it was a secret nobody wanted to tell me."

The case was hardly an outlier. The Premier hospital alliance examined one recent recall and found that even after a device with a potentially dangerous flaw was pulled from the market, physicians at more than 40 hospitals implanted it in at least 50 patients.

"The distressing reality is that we can identify and remove tainted peanut butter and dog food from the market before it reaches consumers, but healthcare patients are at risk of a recalled medical device being used in their treatment because there is no way to quickly and reliably locate a recalled device," said Blair Childs, senior vice president for public affairs at Premier.

Obviously, these mistakes can lead to expensive litigation, often involving charges of negligence, which can result in the awarding of treble damages. These cases also can take a significant toll on a physician's and a hospital's reputation.

These errors can and should become a thing of the past, but only if the hospital industry and medical-device makers work together to make it happen. New regulations, though a major step in the right direction, won't be enough on their own. Healthcare providers need a far better understanding of the risks to patient safety from faulty or expired devices, the lack of accurate documentation of those devices and the full cost implications of widespread inefficiencies in inventory management.

Regulations at last

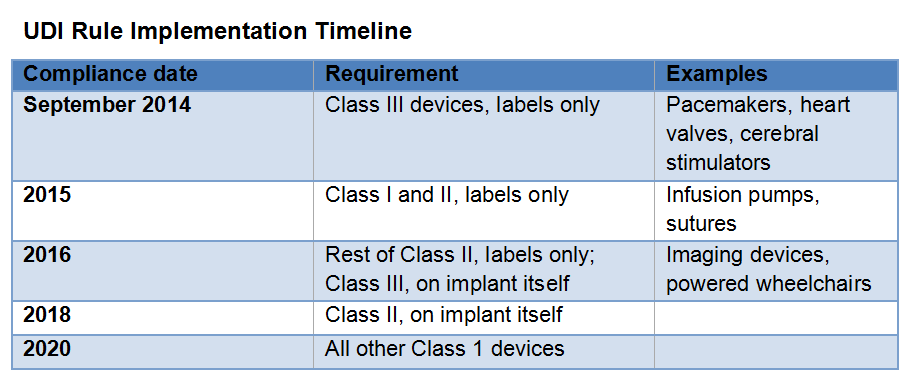

In September 2013, the Food and Drug Administration published its long-awaited final rule establishing a Unique Device Identification system to provide a consistent way to track medical devices throughout their distribution and use. The rule, mandated by the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007, will be phased in over seven years starting in September 2014, when most implantable devices and life-sustaining and life-supporting devices must have standard labels in place.

These labels have to include a device identifier, which is a reference number/product code that attaches to a description of the manufacturer; a production identifier, which has a unique lot number, serial number and expiration date; and a barcode capturing all of that information.

The second component is a publicly searchable database administered by FDA, called the Global Unique Device Identification Database, which will serve as a reference catalogue for every device with an identifier. No identifying patient information will be stored in this device information center.

Although he praised the FDA's action, Mr. Childs, like other observers, lamented the lengthy rollout period. "Since we have already been waiting six years for UDI, it's unfortunate that patients will have to wait until 2020 to have a fully functional device tracking system, particularly since such systems are so pervasive in the retail setting."

Added Joshua Rising, MD, director of medical devices for the Pew Charitable Trusts' medical devices initiative: "Unique device identifiers will enable faster identification of product failures and more comprehensive recalls. But the FDA's rule is just the first step. To fully realize the new system’s benefits, hospitals, health plans and physicians must integrate these codes into patients' health records and insurance billing transactions."

Reports from healthcare group purchasing associations and my own interactions with the industry find that despite the urging of a few industry coalitions, many suppliers and most health systems have yet to act to make the promise of UDI a reality. For years a voluntary private sector effort known as GS1 has been promulgating its version of UDI, but adoption has been slower than expected. We have been hearing suppliers say they will now simply follow the FDA's timeline.

Healthcare providers are under no time pressure at all. Proposed regulations for the meaningful use stage 3 of the federal HITECH Act include a UDI objective for both eligible professionals and hospitals, which must be able to record an approved UDI in the electronic health record at the point of care. However, due to recent delays in implementation, it will be 2017 or later before that would take effect.

As a result, many providers are taking a wait-and-see approach to UDI, even as more patients are harmed by adverse events involving faulty devices.

"It's the, 'What came first, the chicken or the egg?' question," a group purchasing organization executive recently explained. "The hospitals are saying, 'We'll wait until the suppliers get done with what they need to do before we started implementing UDI,' and the suppliers are saying, 'We're going to wait until all the hospitals are ready for my information.'"

This reluctance to act is in many ways hard to understand. After all, barcodes are used throughout healthcare, on patient wristbands, for medication double checks and blood administration. We are all familiar with universal product codes, which have been used in the retail world for nearly 40 years, resulting in annual savings of $17 billion and assisting in countless product recalls.

It has been decades since a checkout clerk or inventory manager has had to key in product information, but in healthcare, 99 percent of all inventory control is manual, resulting in numerous errors and wasted effort.

Also, with today's focus on achieving an optimized, high-value care delivery system, the inability to accurately track which medical products are being used by which clinicians on which patients is especially glaring. Among other issues, the lack of common identification and tracking standards severely hinders comparative effectiveness reviews that could ensure only the safest, highest-quality and most cost-efficient medical devices and drugs are employed in patient care.

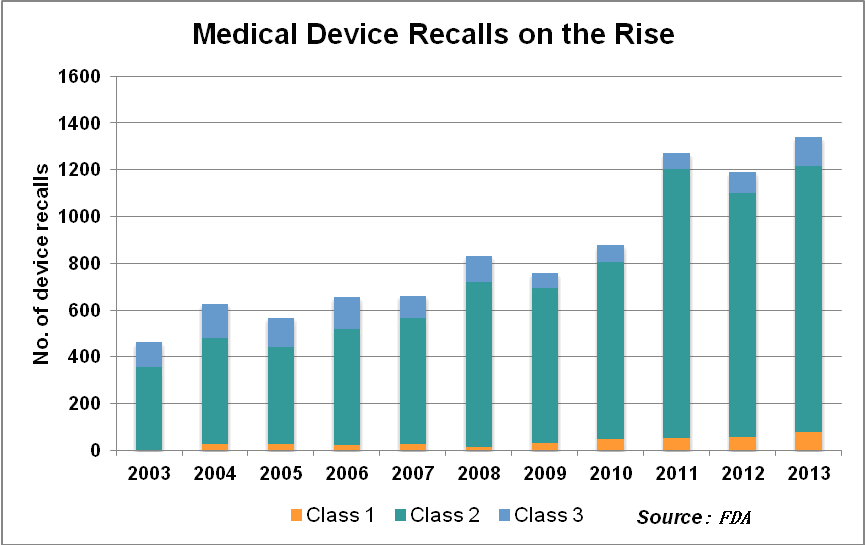

Recalls on the rise

The slow industry uptake on UDI comes amid a surge in product recalls. In the third quarter of 2013 alone, there were 415 medical device recalls, amounting to a total of 29 million units, the FDA reported. The number of patients reported injured in serious adverse events related to medical devices in the U.S. increased by 17 percent per year from 2001-2009, topping 28,000 in 2009, the agency said.

My company estimates that as many as 30 percent of surgical implants are brought in the day of surgery, with little or no time to do the laborious manual legwork required to find out if the device has any reported problems. Currently, more than half of the highest-risk device recalls conclude without all affected patients being notified, products identified in inventories or removed from the market.

There are severe cost implications of inaction. A lack of common product identifiers and data standards has left most providers unaware of what they have in their inventories; products expire while languishing unused and unknown on storeroom shelves or in the "private inventory" of individual clinicians. Procurement is stymied by a large error rate, as providers, distributors and manufacturers can't effectively track usage, need and status.

Manually managing thousands of product recalls each year requires vast expenditure of labor, and even then many devices are missed. Without specific batch information, stakeholders throughout the supply chain often return all of the products, including unaffected ones, to manufacturers.

In October 2012, McKinsey & Co. published research based on interviews with more than 80 healthcare industry leaders around the world that estimated the potential value – in lives and dollars – of adopting a single global identification standard in healthcare. It predicted enabled inventory reduction of up to $94 billion annually, plus reduced costs of managing and storing inventory of $10 billion to $14 billion and reduced product obsolescence of $19 billion to $27 billion.

Rosalind Parkinson, chief supply chain officer at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, points to two other advantages of making full use of UDIs:

- Transaction automation: Processes and systems can be automated, eliminating most of today's manual data entry, validation and correction. Medication and medical device administration could be captured through barcode scanning through UDI tracking systems and automatically fed into logistics, billing and procurement systems that connect all stakeholders, including payers and registries.

- Inventory management collaboration: Dispensing points, distributors and manufacturers could seamlessly exchange medical device or medication usage, location and product availability information. Inventory planning and forecasting programs could analyze the data to optimize inventory levels, improve medication and medical device availability across the supply chain, and ensure that medical products are available at critical moments of treatment.

In 2011, Chesterfield, Mo.-based Mercy Health System, its supply chain arm ROi and supplier Becton Dickinson & Co. collaborated on what may have been the first instance of full integration of GS1 standards across a medical device supply chain. Standards were fully adopted at each step from manufacturing to barcode scanning at the patient bedside. After a significant number of process changes, the organizations achieved a 30 percent reduction in days' payable outstanding; a 73 percent reduction in discrepancies, including a complete elimination of vendor part number and unit of measure discrepancies on purchase orders; and improved sourcing of products.

So what can be done to make sure everyone achieves these results?

For one, as it has done for other areas of patient safety, The Joint Commission could use its accreditation standards process to hasten the widespread adoption of UDIs by providers. After all, the commission already has standards for identifying, tracking, storing and handling human tissue implants.

Providers could also simply act on their own, taking advantage of commercial UDI tracking software services already on the market from my company and others. Waiting beyond the FDA-mandated deadlines seems unacceptable.

Those that do take action can finally be assured that expensive implants aren't wasted, that recalled devices get recalled and that the right medical devices are being used on the right patients for the right (evidenced-based) reasons. It is already many years late, but full adoption of Unique Device Identification would be an essential achievement in the era of accountable care.

Peter I. Casady is president and CEO of Champion Medical Technologies, a Lake Zurich, Ill.-based provider of UDI tracking technology.